文章

ritau

2020年09月04日

Kale, or leaf cabbage, belongs to a group of cabbage (Brassica oleracea) cultivars grown for their edible leaves, although some are used as ornamentals. Kale plants have green or purple leaves, and the central leaves do not form a head (as with headed cabbage). Kales are considered to be closer to wild cabbage than most of the many domesticated forms of Brassica oleracea.

Kale originated in the eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor, where it was cultivated for food beginning by 2000 BCE at the latest. Curly-leaved varieties of cabbage already existed along with flat-leaved varieties in Greece in the 4th century BC. These forms, which were referred to by the Romans as Sabellian kale, are considered to be the ancestors of modern kales.

The earliest record of cabbages in western Europe is of hard-heading cabbage in the 13th century. Records in 14th-century England distinguish between hard-heading cabbage and loose-leaf kale.

Russian kale was introduced into Canada, and then into the United States, by Russian traders in the 19th century. USDA botanist David Fairchild is credited with introducing kale (and many other crops) to Americans, having brought it back from Croatia, although Fairchild himself disliked cabbages, including kale.At the time, kale was widely grown in Croatia mostly because it was easy to grow and inexpensive, and could desalinate soil. For most of the twentieth century, kale was primarily used in the United States for decorative purposes; it became more popular as an edible vegetable in the 1990s due to its nutritional value.

During World War II, the cultivation of kale (and other vegetables) in the U.K. was encouraged by the Dig for Victory campaign. The vegetable was easy to grow and provided important nutrients missing from a diet because of rationing.

Many varieties of kale and cabbage are grown mainly for ornamental leaves that are brilliant white, red, pink, lavender, blue or violet in the interior of the rosette. The different types of ornamental kale are peacock kale, coral prince, kamone coral queen, color up kale and chidori kale. Ornamental kale is as edible as any other variety, but potentially not as palatable. Kale leaves are increasingly used as an ingredient for vegetable bouquets and wedding bouquets.

Raw kale is composed of 84% water, 9% carbohydrates, 4% protein, and 1% fat (table). In a 100 g (3 1⁄2 oz) serving, raw kale provides 207 kilojoules (49 kilocalories) of food energy and a large amount of vitamin K at 3.7 times the Daily Value (DV) (table). It is a rich source (20% or more of the DV) of vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin B6, folate, and manganese. Kale is a good source (10–19% DV) of thiamin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, vitamin E and several dietary minerals, including iron, calcium, potassium, and phosphorus. Boiling raw kale diminishes most of these nutrients, while values for vitamins A, C, and K, and manganese remain substantial.

Kale is a source of the carotenoids, lutein and zeaxanthin. As with broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables, kale contains glucosinolate compounds, such as glucoraphanin, which contributes to the formation of sulforaphane, a compound under preliminary research for its potential to affect human health.

Boiling kale decreases the level of glucosinate compounds, whereas steaming, microwaving or stir frying does not cause significant loss. Kale is high in oxalic acid, the levels of which can be reduced by cooking.

Kale contains high levels of polyphenols, such as ferulic acid, with levels varying due to environmental and genetic factors.

Kale originated in the eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor, where it was cultivated for food beginning by 2000 BCE at the latest. Curly-leaved varieties of cabbage already existed along with flat-leaved varieties in Greece in the 4th century BC. These forms, which were referred to by the Romans as Sabellian kale, are considered to be the ancestors of modern kales.

The earliest record of cabbages in western Europe is of hard-heading cabbage in the 13th century. Records in 14th-century England distinguish between hard-heading cabbage and loose-leaf kale.

Russian kale was introduced into Canada, and then into the United States, by Russian traders in the 19th century. USDA botanist David Fairchild is credited with introducing kale (and many other crops) to Americans, having brought it back from Croatia, although Fairchild himself disliked cabbages, including kale.At the time, kale was widely grown in Croatia mostly because it was easy to grow and inexpensive, and could desalinate soil. For most of the twentieth century, kale was primarily used in the United States for decorative purposes; it became more popular as an edible vegetable in the 1990s due to its nutritional value.

During World War II, the cultivation of kale (and other vegetables) in the U.K. was encouraged by the Dig for Victory campaign. The vegetable was easy to grow and provided important nutrients missing from a diet because of rationing.

Many varieties of kale and cabbage are grown mainly for ornamental leaves that are brilliant white, red, pink, lavender, blue or violet in the interior of the rosette. The different types of ornamental kale are peacock kale, coral prince, kamone coral queen, color up kale and chidori kale. Ornamental kale is as edible as any other variety, but potentially not as palatable. Kale leaves are increasingly used as an ingredient for vegetable bouquets and wedding bouquets.

Raw kale is composed of 84% water, 9% carbohydrates, 4% protein, and 1% fat (table). In a 100 g (3 1⁄2 oz) serving, raw kale provides 207 kilojoules (49 kilocalories) of food energy and a large amount of vitamin K at 3.7 times the Daily Value (DV) (table). It is a rich source (20% or more of the DV) of vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin B6, folate, and manganese. Kale is a good source (10–19% DV) of thiamin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, vitamin E and several dietary minerals, including iron, calcium, potassium, and phosphorus. Boiling raw kale diminishes most of these nutrients, while values for vitamins A, C, and K, and manganese remain substantial.

Kale is a source of the carotenoids, lutein and zeaxanthin. As with broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables, kale contains glucosinolate compounds, such as glucoraphanin, which contributes to the formation of sulforaphane, a compound under preliminary research for its potential to affect human health.

Boiling kale decreases the level of glucosinate compounds, whereas steaming, microwaving or stir frying does not cause significant loss. Kale is high in oxalic acid, the levels of which can be reduced by cooking.

Kale contains high levels of polyphenols, such as ferulic acid, with levels varying due to environmental and genetic factors.

0

0

文章

ritau

2020年06月22日

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the pod fruit Pisum sativum. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and develop from the ovary of a (pea) flower. The name is also used to describe other edible seeds from the Fabaceae such as the pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan), the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), and the seeds from several species of Lathyrus.

P. sativum is an annual plant, with a life cycle of one year. It is a cool-season crop grown in many parts of the world; planting can take place from winter to early summer depending on location. The average pea weighs between 0.1 and 0.36 gram. The immature peas (and in snow peas the tender pod as well) are used as a vegetable, fresh, frozen or canned; varieties of the species typically called field peas are grown to produce dry peas like the split pea shelled from a matured pod. These are the basis of pease porridge and pea soup, staples of medieval cuisine; in Europe, consuming fresh immature green peas was an innovation of Early Modern cuisine.

The wild pea is restricted to the Mediterranean basin and the Near East. The earliest archaeological finds of peas date from the late Neolithic era of current Greece, Syria, Turkey and Jordan. In Egypt, early finds date from c. 4800–4400 BC in the Nile delta area, and from c. 3800–3600 BC in Upper Egypt. The pea was also present in Georgia in the 5th millennium BC. Farther east, the finds are younger. Peas were present in Afghanistan c. 2000 BC; in Harappan civilization around modern-day Pakistan and western- and northwestern India in 2250–1750 BC. In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, this legume crop appears in the Ganges Basin and southern India.

In early times, peas were grown mostly for their dry seeds. From plants growing wild in the Mediterranean basin, constant selection since the Neolithic dawn of agriculture improved their yield. In the early 3rd century BC Theophrastus mentions peas among the legumes that are sown late in the winter because of their tenderness. In the first century AD, Columella mentions them in De re rustica, when Roman legionaries still gathered wild peas from the sandy soils of Numidia and Judea to supplement their rations.

In the Middle Ages, field peas are constantly mentioned, as they were the staple that kept famine at bay, as Charles the Good, count of Flanders, noted explicitly in 1124.

Green "garden" peas, eaten immature and fresh, were an innovative luxury of Early Modern Europe. In England, the distinction between field peas and garden peas dates from the early 17th century: John Gerard and John Parkinson both mention garden peas. Sugar peas, which the French called mange-tout, for they were consumed pods and all, were introduced to France from the market gardens of Holland in the time of Henri IV, through the French ambassador. Green peas were introduced from Genoa to the court of Louis XIV of France in January 1660, with some staged fanfare; a hamper of them were presented before the King, and then were shelled by the Savoyan comte de Soissons, who had married a niece of Cardinal Mazarin; little dishes of peas were then presented to the King, the Queen, Cardinal Mazarin and Monsieur, the king's brother. Immediately established and grown for earliness warmed with manure and protected under glass, they were still a luxurious delicacy in 1696, when Mme de Maintenon and Mme de Sevigné each reported that they were "a fashion, a fury".

Modern split peas, with their indigestible skins rubbed off, are a development of the later 19th century.

Peas are starchy, but high in fiber, protein, vitamin A, vitamin B6, vitamin C, vitamin K, phosphorus, magnesium, copper, iron, zinc and lutein.Dry weight is about one-quarter protein and one-quarter sugar. Pea seed peptide fractions have less ability to scavenge free radicals than glutathione, but greater ability to chelate metals and inhibit linoleic acid oxidation.

P. sativum is an annual plant, with a life cycle of one year. It is a cool-season crop grown in many parts of the world; planting can take place from winter to early summer depending on location. The average pea weighs between 0.1 and 0.36 gram. The immature peas (and in snow peas the tender pod as well) are used as a vegetable, fresh, frozen or canned; varieties of the species typically called field peas are grown to produce dry peas like the split pea shelled from a matured pod. These are the basis of pease porridge and pea soup, staples of medieval cuisine; in Europe, consuming fresh immature green peas was an innovation of Early Modern cuisine.

The wild pea is restricted to the Mediterranean basin and the Near East. The earliest archaeological finds of peas date from the late Neolithic era of current Greece, Syria, Turkey and Jordan. In Egypt, early finds date from c. 4800–4400 BC in the Nile delta area, and from c. 3800–3600 BC in Upper Egypt. The pea was also present in Georgia in the 5th millennium BC. Farther east, the finds are younger. Peas were present in Afghanistan c. 2000 BC; in Harappan civilization around modern-day Pakistan and western- and northwestern India in 2250–1750 BC. In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, this legume crop appears in the Ganges Basin and southern India.

In early times, peas were grown mostly for their dry seeds. From plants growing wild in the Mediterranean basin, constant selection since the Neolithic dawn of agriculture improved their yield. In the early 3rd century BC Theophrastus mentions peas among the legumes that are sown late in the winter because of their tenderness. In the first century AD, Columella mentions them in De re rustica, when Roman legionaries still gathered wild peas from the sandy soils of Numidia and Judea to supplement their rations.

In the Middle Ages, field peas are constantly mentioned, as they were the staple that kept famine at bay, as Charles the Good, count of Flanders, noted explicitly in 1124.

Green "garden" peas, eaten immature and fresh, were an innovative luxury of Early Modern Europe. In England, the distinction between field peas and garden peas dates from the early 17th century: John Gerard and John Parkinson both mention garden peas. Sugar peas, which the French called mange-tout, for they were consumed pods and all, were introduced to France from the market gardens of Holland in the time of Henri IV, through the French ambassador. Green peas were introduced from Genoa to the court of Louis XIV of France in January 1660, with some staged fanfare; a hamper of them were presented before the King, and then were shelled by the Savoyan comte de Soissons, who had married a niece of Cardinal Mazarin; little dishes of peas were then presented to the King, the Queen, Cardinal Mazarin and Monsieur, the king's brother. Immediately established and grown for earliness warmed with manure and protected under glass, they were still a luxurious delicacy in 1696, when Mme de Maintenon and Mme de Sevigné each reported that they were "a fashion, a fury".

Modern split peas, with their indigestible skins rubbed off, are a development of the later 19th century.

Peas are starchy, but high in fiber, protein, vitamin A, vitamin B6, vitamin C, vitamin K, phosphorus, magnesium, copper, iron, zinc and lutein.Dry weight is about one-quarter protein and one-quarter sugar. Pea seed peptide fractions have less ability to scavenge free radicals than glutathione, but greater ability to chelate metals and inhibit linoleic acid oxidation.

0

0

文章

ritau

2020年05月12日

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) is a leafy green flowering plant native to central and western Asia. It is of the order Caryophyllales, family Amaranthaceae, subfamily Chenopodioideae. Its leaves are a common edible vegetable consumed either fresh, or after storage using preservation techniques by canning, freezing, or dehydration. It may be eaten cooked or raw, and the taste differs considerably; the high oxalate content may be reduced by steaming.

It is an annual plant (rarely biennial), growing as tall as 30 cm (1 ft). Spinach may overwinter in temperate regions. The leaves are alternate, simple, ovate to triangular, and very variable in size: 2–30 cm (1–12 in) long and 1–15 cm (0.4–5.9 in) broad, with larger leaves at the base of the plant and small leaves higher on the flowering stem. The flowers are inconspicuous, yellow-green, 3–4 mm (0.1–0.2 in) in diameter, and mature into a small, hard, dry, lumpy fruit cluster 5–10 mm (0.2–0.4 in) across containing several seeds.

*Nutrients*

Raw spinach is 91% water, 4% carbohydrates, 3% protein, and contains negligible fat. In a 100 g (3.5 oz) serving providing only 23 calories, spinach has a high nutritional value, especially when fresh, frozen, steamed, or quickly boiled. It is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin K, magnesium, manganese, iron and folate. Spinach is a good source (10-19% of DV) of the B vitamins riboflavin and vitamin B6, vitamin E, calcium, potassium, and dietary fiber. Although spinach is touted as being high in iron and calcium content, and is often served and consumed in its raw form, raw spinach contains high levels of oxalates, which block absorption of calcium and iron in the stomach and small intestine. Spinach cooked in several changes of water has much lower levels of oxalates and is better digested and its nutrients absorbed more completely.

-Iron

Spinach, along with other green, leafy vegetables, contains an appreciable amount of iron attaining 21% of the Daily Value in a 100 g (3.5 oz) amount of raw spinach. For example, the United States Department of Agriculture states that a 100 g (3.5 oz) serving of cooked spinach contains 3.57 mg of iron, whereas a 100 g (3.5 oz) ground hamburger patty contains 1.93 mg of iron. However, spinach contains iron absorption-inhibiting substances, including high levels of oxalate, which can bind to the iron to form ferrous oxalate and render much of the iron in spinach unusable by the body.In addition to preventing absorption and use, high levels of oxalates remove iron from the body.

-Calcium

Spinach also has a moderate calcium content which can be affected by oxalates, decreasing its absorption. The calcium in spinach is among the least bioavailable of food calcium sources. By way of comparison, the human body can absorb about half of the calcium present in broccoli, yet only around 5% of the calcium in spinach.

-Vitamin K

A quantity of 3.5 ounces of spinach contains over four times the recommended daily intake of vitamin K. For this reason, individuals taking the anticoagulant warfarin – which acts by inhibiting vitamin K – are instructed to minimize consumption of spinach (as well as other dark green leafy vegetables) to avoid blunting the effect of warfarin.

It is an annual plant (rarely biennial), growing as tall as 30 cm (1 ft). Spinach may overwinter in temperate regions. The leaves are alternate, simple, ovate to triangular, and very variable in size: 2–30 cm (1–12 in) long and 1–15 cm (0.4–5.9 in) broad, with larger leaves at the base of the plant and small leaves higher on the flowering stem. The flowers are inconspicuous, yellow-green, 3–4 mm (0.1–0.2 in) in diameter, and mature into a small, hard, dry, lumpy fruit cluster 5–10 mm (0.2–0.4 in) across containing several seeds.

*Nutrients*

Raw spinach is 91% water, 4% carbohydrates, 3% protein, and contains negligible fat. In a 100 g (3.5 oz) serving providing only 23 calories, spinach has a high nutritional value, especially when fresh, frozen, steamed, or quickly boiled. It is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin K, magnesium, manganese, iron and folate. Spinach is a good source (10-19% of DV) of the B vitamins riboflavin and vitamin B6, vitamin E, calcium, potassium, and dietary fiber. Although spinach is touted as being high in iron and calcium content, and is often served and consumed in its raw form, raw spinach contains high levels of oxalates, which block absorption of calcium and iron in the stomach and small intestine. Spinach cooked in several changes of water has much lower levels of oxalates and is better digested and its nutrients absorbed more completely.

-Iron

Spinach, along with other green, leafy vegetables, contains an appreciable amount of iron attaining 21% of the Daily Value in a 100 g (3.5 oz) amount of raw spinach. For example, the United States Department of Agriculture states that a 100 g (3.5 oz) serving of cooked spinach contains 3.57 mg of iron, whereas a 100 g (3.5 oz) ground hamburger patty contains 1.93 mg of iron. However, spinach contains iron absorption-inhibiting substances, including high levels of oxalate, which can bind to the iron to form ferrous oxalate and render much of the iron in spinach unusable by the body.In addition to preventing absorption and use, high levels of oxalates remove iron from the body.

-Calcium

Spinach also has a moderate calcium content which can be affected by oxalates, decreasing its absorption. The calcium in spinach is among the least bioavailable of food calcium sources. By way of comparison, the human body can absorb about half of the calcium present in broccoli, yet only around 5% of the calcium in spinach.

-Vitamin K

A quantity of 3.5 ounces of spinach contains over four times the recommended daily intake of vitamin K. For this reason, individuals taking the anticoagulant warfarin – which acts by inhibiting vitamin K – are instructed to minimize consumption of spinach (as well as other dark green leafy vegetables) to avoid blunting the effect of warfarin.

0

0

文章

ritau

2020年05月06日

Broccoli is an edible green plant in the cabbage family (family Brassicaceae, genus Brassica) whose large flowering head and stalk is eaten as a vegetable. The word broccoli comes from the Italian plural of broccolo, which means "the flowering crest of a cabbage", and is the diminutive form of brocco, meaning "small nail" or "sprout".

Broccoli is classified in the Italica cultivar group of the species Brassica oleracea. Broccoli has large flower heads, usually dark green in color, arranged in a tree-like structure branching out from a thick stalk which is usually light green. The mass of flower heads is surrounded by leaves. Broccoli resembles cauliflower, which is a different cultivar group of the same Brassica species. Combined in 2017, China and India produced 73% of the world's broccoli and cauliflower crops.

Broccoli resulted from breeding of cultivated Brassica crops in the northern Mediterranean starting in about the sixth century BC. Broccoli has its origins in primitive cultivars grown in the Roman Empire.It is eaten raw or cooked. Broccoli is a particularly rich source of vitamin C and vitamin K. Contents of its characteristic sulfur-containing glucosinolate compounds, isothiocyanates and sulforaphane, are diminished by boiling, but are better preserved by steaming, microwaving or stir-frying.

A 100 gram reference serving of raw broccoli provides 34 calories and is a rich source (20% or higher of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin C (107% DV) and vitamin K (97% DV) (table). Raw broccoli also contains moderate amounts (10–19% DV) of several B vitamins and the dietary mineral manganese, whereas other micronutrients are low in content (less than 10% DV). Raw broccoli is 89% water, 7% carbohydrates, 3% protein, and contains negligible fat (table).

Boiling substantially reduces the levels of broccoli glucosinolates, while other cooking methods, such as steaming, microwaving, and stir frying, have no significant effect on glucosinolate levels.

Broccoli is classified in the Italica cultivar group of the species Brassica oleracea. Broccoli has large flower heads, usually dark green in color, arranged in a tree-like structure branching out from a thick stalk which is usually light green. The mass of flower heads is surrounded by leaves. Broccoli resembles cauliflower, which is a different cultivar group of the same Brassica species. Combined in 2017, China and India produced 73% of the world's broccoli and cauliflower crops.

Broccoli resulted from breeding of cultivated Brassica crops in the northern Mediterranean starting in about the sixth century BC. Broccoli has its origins in primitive cultivars grown in the Roman Empire.It is eaten raw or cooked. Broccoli is a particularly rich source of vitamin C and vitamin K. Contents of its characteristic sulfur-containing glucosinolate compounds, isothiocyanates and sulforaphane, are diminished by boiling, but are better preserved by steaming, microwaving or stir-frying.

A 100 gram reference serving of raw broccoli provides 34 calories and is a rich source (20% or higher of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin C (107% DV) and vitamin K (97% DV) (table). Raw broccoli also contains moderate amounts (10–19% DV) of several B vitamins and the dietary mineral manganese, whereas other micronutrients are low in content (less than 10% DV). Raw broccoli is 89% water, 7% carbohydrates, 3% protein, and contains negligible fat (table).

Boiling substantially reduces the levels of broccoli glucosinolates, while other cooking methods, such as steaming, microwaving, and stir frying, have no significant effect on glucosinolate levels.

0

0

文章

ritau

2020年04月08日

Have you ever seen a Marimo, the cute moss ball?

Marimo (also known as Cladophora ball, moss ball, moss ball pets, or lake ball) is a rare growth form of Aegagropila linnaei (a species of filamentous green algae) in which the algae grow into large green balls with a velvety appearance. Marimo are eukaryotic.

The species can be found in a number of lakes and rivers in Japan and Northern Europe. Colonies of marimo balls are known to form in Japan and Iceland, but their population has been declining.

Marimo were first described in the 1820s by Anton E. Sauter, found in Lake Zell, Austria. The genus Aegagropila was established by Friedrich T. Kützing (1843) with A. linnaei as the type species based on its formation of spherical aggregations, but all the Aegagropila species were transferred to subgenus Aegagropila of genus Cladophora later by the same author (Kützing 1849). Subsequently, A. linnaei was placed in the genus Cladophora in the Cladophorales and was renamed Cladophora aegagropila (L.) Rabenhorst and Cl. sauteri (Nees ex Kütz.) Kütz. Extensive DNA research in 2002 returned the name to Aegagropila linnaei. The presence of chitin in the cell walls makes it distinct from the genus Cladophora.

The plant was named marimo by the Japanese botanist Takiya Kawakami in 1898. Mari is a bouncy play ball. Mo is a generic term for plants that grow in water. The native names in Ainu are torasampe (lake goblin) and tokarip (lake roller). They are sometimes sold in aquariums under the name "Japanese moss balls" although they are unrelated to moss. In Iceland the lake balls are called kúluskítur by the local fishermen at Lake Mývatn (kúla = ball, skítur = muck) where the "muck" is any weeds that get entangled in their fishing nets. The generic name Aegagropila is Greek for "goat hair".

Marimo's preferred habitat is in lakes with a low or moderate biological activity, and with moderate or high levels of calcium.

The species is sensitive to the amount of nutrients in the water. An excess of nutrients (due to agriculture and fish farming), along with mud deposition from human activity are thought to be the main causes for its disappearance from many lakes.The species still exists in Lake Zeller in Austria (where it was first discovered in the 1820s) but the lake ball growth form has not been found there since around 1910. The same has happened in most locations in England and Scotland, where mainly the attached form can be found.Dense colonies of marimo were discovered in Lake Mývatn in Iceland in 1978, but they have shrunk considerably since then. By 2014 the marimo had almost completely disappeared from the lake due to an excess of nutrients.The species can still be found in several places in Japan, but populations have also declined there. At Lake Akan, a great effort is spent on the conservation of the lake balls.The marimo has been a protected species in Japan since the 1920s, and in Iceland since 2006. Lake Akan is protected as a national park and Lake Mývatn is protected as a nature reserve.

Marimo balls are a rare curiosity. In Japan, the Ainu people hold a three-day marimo festival every October at Lake Akan.

Because of their appealing appearance, the lake balls also serve as a medium for environmental education. Small balls sold as souvenirs are hand rolled from free-floating filaments.A widely marketed stuffed toy character known as Marimokkori takes the anthropomorphic form of the marimo algae as one part of its design.Marimo are sometimes sold for display in aquariums, those often originate from Ukrainian lakes like the Shatsk's lakes. Balls sold in Japanese aquarium shops are of European origin, collecting them from Lake Akan is prohibited.

Let us protect the cute Marimo!

Marimo (also known as Cladophora ball, moss ball, moss ball pets, or lake ball) is a rare growth form of Aegagropila linnaei (a species of filamentous green algae) in which the algae grow into large green balls with a velvety appearance. Marimo are eukaryotic.

The species can be found in a number of lakes and rivers in Japan and Northern Europe. Colonies of marimo balls are known to form in Japan and Iceland, but their population has been declining.

Marimo were first described in the 1820s by Anton E. Sauter, found in Lake Zell, Austria. The genus Aegagropila was established by Friedrich T. Kützing (1843) with A. linnaei as the type species based on its formation of spherical aggregations, but all the Aegagropila species were transferred to subgenus Aegagropila of genus Cladophora later by the same author (Kützing 1849). Subsequently, A. linnaei was placed in the genus Cladophora in the Cladophorales and was renamed Cladophora aegagropila (L.) Rabenhorst and Cl. sauteri (Nees ex Kütz.) Kütz. Extensive DNA research in 2002 returned the name to Aegagropila linnaei. The presence of chitin in the cell walls makes it distinct from the genus Cladophora.

The plant was named marimo by the Japanese botanist Takiya Kawakami in 1898. Mari is a bouncy play ball. Mo is a generic term for plants that grow in water. The native names in Ainu are torasampe (lake goblin) and tokarip (lake roller). They are sometimes sold in aquariums under the name "Japanese moss balls" although they are unrelated to moss. In Iceland the lake balls are called kúluskítur by the local fishermen at Lake Mývatn (kúla = ball, skítur = muck) where the "muck" is any weeds that get entangled in their fishing nets. The generic name Aegagropila is Greek for "goat hair".

Marimo's preferred habitat is in lakes with a low or moderate biological activity, and with moderate or high levels of calcium.

The species is sensitive to the amount of nutrients in the water. An excess of nutrients (due to agriculture and fish farming), along with mud deposition from human activity are thought to be the main causes for its disappearance from many lakes.The species still exists in Lake Zeller in Austria (where it was first discovered in the 1820s) but the lake ball growth form has not been found there since around 1910. The same has happened in most locations in England and Scotland, where mainly the attached form can be found.Dense colonies of marimo were discovered in Lake Mývatn in Iceland in 1978, but they have shrunk considerably since then. By 2014 the marimo had almost completely disappeared from the lake due to an excess of nutrients.The species can still be found in several places in Japan, but populations have also declined there. At Lake Akan, a great effort is spent on the conservation of the lake balls.The marimo has been a protected species in Japan since the 1920s, and in Iceland since 2006. Lake Akan is protected as a national park and Lake Mývatn is protected as a nature reserve.

Marimo balls are a rare curiosity. In Japan, the Ainu people hold a three-day marimo festival every October at Lake Akan.

Because of their appealing appearance, the lake balls also serve as a medium for environmental education. Small balls sold as souvenirs are hand rolled from free-floating filaments.A widely marketed stuffed toy character known as Marimokkori takes the anthropomorphic form of the marimo algae as one part of its design.Marimo are sometimes sold for display in aquariums, those often originate from Ukrainian lakes like the Shatsk's lakes. Balls sold in Japanese aquarium shops are of European origin, collecting them from Lake Akan is prohibited.

Let us protect the cute Marimo!

0

0

文章

ritau

2020年03月31日

There are many plants that can be regrown indoors, which is very convenient for green hands to try gardening. Today, we are going to introduce 7 kinds of plants to you to regrow in water. Let’s take a look!

1.Carrots Greens

Instead of defaulting to the compost, use carrot tops to grow healthy carrot greens. Place a carrot top or tops in a bowl, cut side down. Fill the bowl with about an inch of water so the top is halfway covered. Place the dish in a sunny windowsill and change the water every day.

The tops will eventually sprout shoots. When they do, plant the tops in soil, careful not to cover the shoots. Harvest the greens to taste. (Some people prefer the baby greens; others prefer them fully grown.)

(Instructions via Gardening Know-How)

2.Green Onion

Instead of tossing the green part of these veggies, use them to grow more. Place the greens in a cup or recycled jar filled with water. Put the cup or jar on a windowsill and change the water every other day. In about a week, you should have a new green onion, leek, and/or scallion to add to your supper. Harvest when fullygrown—just make sure to leave the roots in the water.

(Instructions via Living Green Magazine)

3.Bok Choy

Cut off the base of a bok choy plant and place it in a bowl bottom-down. Add a small amount of water in the bowl. Cover the whole base with water, but do not add more than 1/4 inch above the base. Replace water every few days. In about one week, you should see regrowth around the center of the base.

Once you see regrowth, transfer the plant to a container or garden. Cover everything except the new growth with soil. Your bok choy should be full grown and ready to harvest in approximately five months.

(Instructions via My Heart Beets)

4.Celery

Rinse off the base of a bunch of celery and place it in a small bowl or similar container (any wide-mouthed, glass, or ceramic container should do). Fill the container with warm water, cut stalks facing upright. Place the bowl in a sunny area. Leave the base as-is for about one week and change the water every other day. Use a spray bottle to gently mist the plant every other day. The tiny yellow leaves around the center of the base will grow thicker and turn dark green.

After five to seven days, move the celery base to a planter or garden and cover it with soil, leaving the leaf tips uncovered. Keep the plant well watered. You’ll soon notice celery leaves regenerate from the base, as well as a few small stalks. Harvest when fully grown, then repeat the process.

(Instructions via 17 Apart)

5.Romaine Lettuce

When you chop up hearts of romaine, set aside a few inches from the bottom of the heart. Place in a bowl with about a ½ inch of water. Keep the bowl in a sunny area and change the water every day.

In a few days, you’ll start to notice sprouts. Plant the sprouted hearts directly in the garden. If you like the taste of baby greens, you can pinch off outer leaves as the lettuce grows. Otherwise, harvest romaine when it’s around 6 to 8 inches tall. If you want to continue growing lettuce, cut the romaine heads off right above the soil line with a sharp knife, leaving the base and root system intact. Otherwise, uproot the whole plant.

(Instructions via Lifehacker)

6.Lemongrass

A frequent component of Thai dishes, lemongrass is a great addition to marinades, stir-fries, spice rubs, and curry pastes. To grow your own from scraps, cut off the tops of a bunch of lemongrass and place the stalks in water. Change the water every few days. In approximately two or three weeks, you should see new roots.

When the stems have developed strong root growth, plant the stalks in a pot or garden (preferably in an area that receives lots of sun). Because lemongrass needs to stay warm year round, plant the stalks in a container that can be moved inside during the winter months. Harvest lemongrass once it reaches one foot in height; just cut off the amount you need, being careful not to uproot the plant.

(Instructions via Suited to the Seasons)

7.Garlic Sprout

While you may not be able to grow garlic bulbs, you can grow garlic sprouts—also known as garlic greens—from a clove or bulb. Place a budding clove (or even a whole bulb) in a small cup, bowl, or jar. Add water until it covers the bottom of the container and touches the bottom of the cloves. Be careful not to submerge the cloves in order to avoid rot. Change the water every other day and place in a sunny area.

After a few days, the clove or bulb will start to produce roots. Sprouts may grow as long as 10 inches, but snip off the greens once they’re around 3 inches tall. Just be sure not to remove more than one-third of each sprout at one time. They’re tasty on top of baked potatoes, salads, in dips, or as a simple garnish.

(Instructions via Simple Daily Recipes)

Hope you can enjoy your harvest!

1.Carrots Greens

Instead of defaulting to the compost, use carrot tops to grow healthy carrot greens. Place a carrot top or tops in a bowl, cut side down. Fill the bowl with about an inch of water so the top is halfway covered. Place the dish in a sunny windowsill and change the water every day.

The tops will eventually sprout shoots. When they do, plant the tops in soil, careful not to cover the shoots. Harvest the greens to taste. (Some people prefer the baby greens; others prefer them fully grown.)

(Instructions via Gardening Know-How)

2.Green Onion

Instead of tossing the green part of these veggies, use them to grow more. Place the greens in a cup or recycled jar filled with water. Put the cup or jar on a windowsill and change the water every other day. In about a week, you should have a new green onion, leek, and/or scallion to add to your supper. Harvest when fullygrown—just make sure to leave the roots in the water.

(Instructions via Living Green Magazine)

3.Bok Choy

Cut off the base of a bok choy plant and place it in a bowl bottom-down. Add a small amount of water in the bowl. Cover the whole base with water, but do not add more than 1/4 inch above the base. Replace water every few days. In about one week, you should see regrowth around the center of the base.

Once you see regrowth, transfer the plant to a container or garden. Cover everything except the new growth with soil. Your bok choy should be full grown and ready to harvest in approximately five months.

(Instructions via My Heart Beets)

4.Celery

Rinse off the base of a bunch of celery and place it in a small bowl or similar container (any wide-mouthed, glass, or ceramic container should do). Fill the container with warm water, cut stalks facing upright. Place the bowl in a sunny area. Leave the base as-is for about one week and change the water every other day. Use a spray bottle to gently mist the plant every other day. The tiny yellow leaves around the center of the base will grow thicker and turn dark green.

After five to seven days, move the celery base to a planter or garden and cover it with soil, leaving the leaf tips uncovered. Keep the plant well watered. You’ll soon notice celery leaves regenerate from the base, as well as a few small stalks. Harvest when fully grown, then repeat the process.

(Instructions via 17 Apart)

5.Romaine Lettuce

When you chop up hearts of romaine, set aside a few inches from the bottom of the heart. Place in a bowl with about a ½ inch of water. Keep the bowl in a sunny area and change the water every day.

In a few days, you’ll start to notice sprouts. Plant the sprouted hearts directly in the garden. If you like the taste of baby greens, you can pinch off outer leaves as the lettuce grows. Otherwise, harvest romaine when it’s around 6 to 8 inches tall. If you want to continue growing lettuce, cut the romaine heads off right above the soil line with a sharp knife, leaving the base and root system intact. Otherwise, uproot the whole plant.

(Instructions via Lifehacker)

6.Lemongrass

A frequent component of Thai dishes, lemongrass is a great addition to marinades, stir-fries, spice rubs, and curry pastes. To grow your own from scraps, cut off the tops of a bunch of lemongrass and place the stalks in water. Change the water every few days. In approximately two or three weeks, you should see new roots.

When the stems have developed strong root growth, plant the stalks in a pot or garden (preferably in an area that receives lots of sun). Because lemongrass needs to stay warm year round, plant the stalks in a container that can be moved inside during the winter months. Harvest lemongrass once it reaches one foot in height; just cut off the amount you need, being careful not to uproot the plant.

(Instructions via Suited to the Seasons)

7.Garlic Sprout

While you may not be able to grow garlic bulbs, you can grow garlic sprouts—also known as garlic greens—from a clove or bulb. Place a budding clove (or even a whole bulb) in a small cup, bowl, or jar. Add water until it covers the bottom of the container and touches the bottom of the cloves. Be careful not to submerge the cloves in order to avoid rot. Change the water every other day and place in a sunny area.

After a few days, the clove or bulb will start to produce roots. Sprouts may grow as long as 10 inches, but snip off the greens once they’re around 3 inches tall. Just be sure not to remove more than one-third of each sprout at one time. They’re tasty on top of baked potatoes, salads, in dips, or as a simple garnish.

(Instructions via Simple Daily Recipes)

Hope you can enjoy your harvest!

0

0

文章

ritau

2020年02月23日

In botany, chlorosis is a condition in which leaves produce insufficient chlorophyll. As chlorophyll is responsible for the green color of leaves, chlorotic leaves are pale, yellow, or yellow-white. The affected plant has little or no ability to manufacture carbohydrates through photosynthesis and may die unless the cause of its chlorophyll insufficiency is treated and this may lead to a plant diseases called rusts, although some chlorotic plants, such as the albino Arabidopsis thaliana mutant ppi2, are viable if supplied with exogenous sucrose.

Chlorosis is derived from the Greek khloros meaning 'greenish-yellow', 'pale green', 'pale', 'pallid', or 'fresh'.

In viticulture, the most common symptom of poor nutrition in grapevines is the yellowing of grape leaves caused by chlorosis and the subsequent loss of chlorophyll. This is often seen in vineyard soils that are high in limestone such as the Italian wine region of Barolo in the Piedmont, the Spanish wine region of Rioja and the French wine regions of Champagne and Burgundy. In these soils the grapevine often struggles to pull sufficient levels of iron which is a needed component in the production of chlorophyll.

Chlorosis is typically caused when leaves do not have enough nutrients to synthesise all the chlorophyll they need. It can be brought about by a combination of factors including:

* a specific mineral deficiency in the soil, such as iron,magnesium or zinc

* deficient nitrogen and/or proteins

* a soil pH at which minerals become unavailable for absorption by the roots

* poor drainage (waterlogged roots)

* damaged and/or compacted roots

* pesticides and particularly herbicides may cause chlorosis, both to target weeds and occasionally to the crop being treated.

* exposure to sulphur dioxide

* ozone injury to sensitive plants

* presence of any number of bacterial pathogens, for instance Pseudomonas syringae pv. tagetis that causes complete chlorosis on Asteraceae

* fungal infection, e.g. Bakanae.

* However, the exact conditions vary from plant type to plant type. For example, Azaleas grow best in acidic soil and rice is unharmed by waterlogged soil.

Specific nutrient deficiencies (often aggravated by high soil pH) may be corrected by supplemental feedings of iron, in the form of a chelate or sulphate, magnesium or nitrogen compounds in various combinations.

Chlorosis is derived from the Greek khloros meaning 'greenish-yellow', 'pale green', 'pale', 'pallid', or 'fresh'.

In viticulture, the most common symptom of poor nutrition in grapevines is the yellowing of grape leaves caused by chlorosis and the subsequent loss of chlorophyll. This is often seen in vineyard soils that are high in limestone such as the Italian wine region of Barolo in the Piedmont, the Spanish wine region of Rioja and the French wine regions of Champagne and Burgundy. In these soils the grapevine often struggles to pull sufficient levels of iron which is a needed component in the production of chlorophyll.

Chlorosis is typically caused when leaves do not have enough nutrients to synthesise all the chlorophyll they need. It can be brought about by a combination of factors including:

* a specific mineral deficiency in the soil, such as iron,magnesium or zinc

* deficient nitrogen and/or proteins

* a soil pH at which minerals become unavailable for absorption by the roots

* poor drainage (waterlogged roots)

* damaged and/or compacted roots

* pesticides and particularly herbicides may cause chlorosis, both to target weeds and occasionally to the crop being treated.

* exposure to sulphur dioxide

* ozone injury to sensitive plants

* presence of any number of bacterial pathogens, for instance Pseudomonas syringae pv. tagetis that causes complete chlorosis on Asteraceae

* fungal infection, e.g. Bakanae.

* However, the exact conditions vary from plant type to plant type. For example, Azaleas grow best in acidic soil and rice is unharmed by waterlogged soil.

Specific nutrient deficiencies (often aggravated by high soil pH) may be corrected by supplemental feedings of iron, in the form of a chelate or sulphate, magnesium or nitrogen compounds in various combinations.

0

0

文章

绿手指客服

2019年12月24日

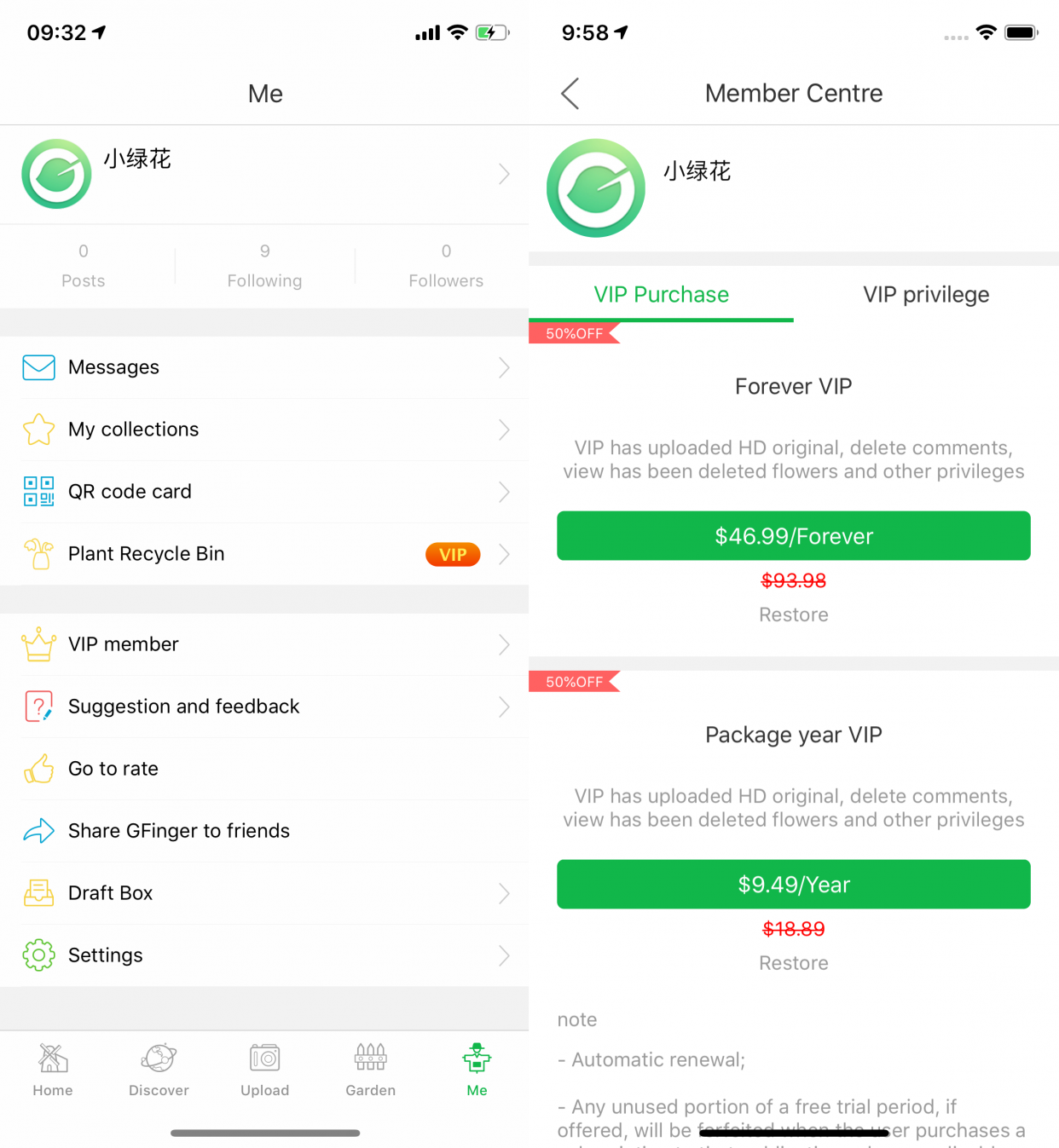

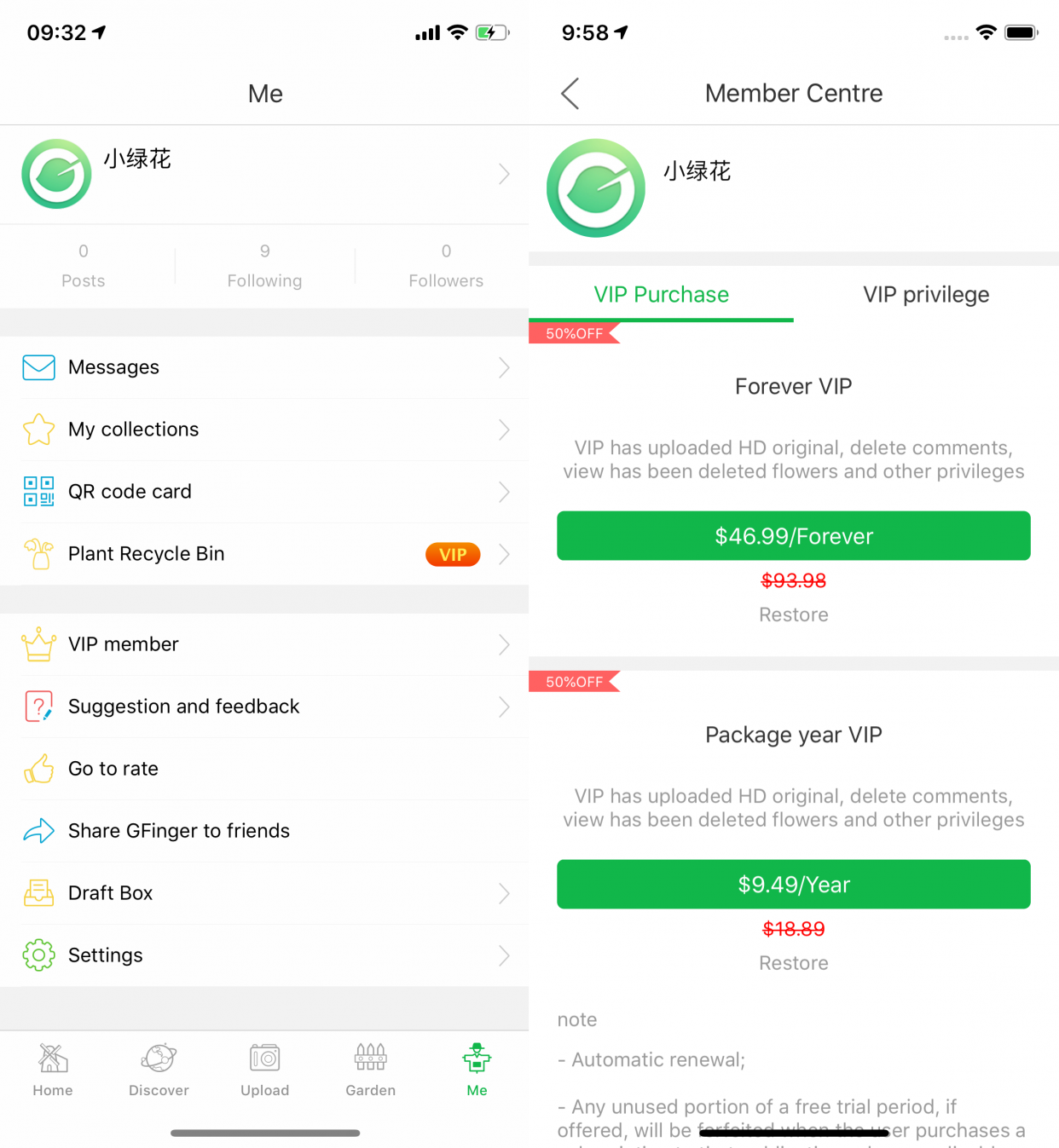

Your annual Christmas event is coming!

The biggest discounts throughout the year! The longest!

Green Finger VIP

50% discount!

Activity is limited to 10 days! Rare opportunity!

Activity time 2019.12.23-2020.01.01

Merry Christmas, everyone!

The biggest discounts throughout the year! The longest!

Green Finger VIP

50% discount!

Activity is limited to 10 days! Rare opportunity!

Activity time 2019.12.23-2020.01.01

Merry Christmas, everyone!

0

0

采蘑菇的小幸运900:您好

文章

A🎌王木木💮

2019年10月28日

Every month has its own lucky flower,The lucky flower of October is the Cosmos bipinnata .Bright green fernlike foliage is the perfect complement to the daisylike flowers of cosmos, which come in shades of white, pink, yellow, or orange.

This cottage-garden favorite is a magnet for pollinators and easily grown from seed sown directly in the garden. Plant petite varieties, such as ‘Little Ladybirds’, in containers for a pretty splash of color on the patio. Because cosmos is so easy to grow, it is a fun choice for a children’s garden. Today we will talk about theCosmos sulphureus.

Other common names: yellow cosmos 'Tango'

Family:Asteraceae

Genus:Cosmos can be annuals or perennials with simple or pinnately divided leaves and large, long-stalked daisy-like flowers in summer

Details:'Tango' is an erect, half-hardy annual, to 1.2m tall, with finely-divided mid-green leaves and semi-double flowers in shades of orange, with yellow centres, from summer into autumn

How to grow

Cultivation Grow in moderately fertile, moist but well-drained soil in full sun

PropagationPropagate by seed in mid spring

Suggested planting locations and garden types Cut Flowers Flower borders and beds Cottage & Informal Garden

How to care

PruningDeadheading should be carried out regularly to prolong flowering

PestsAphids and slugs may be a nuisance

Diseases May be affected by grey moulds

This cottage-garden favorite is a magnet for pollinators and easily grown from seed sown directly in the garden. Plant petite varieties, such as ‘Little Ladybirds’, in containers for a pretty splash of color on the patio. Because cosmos is so easy to grow, it is a fun choice for a children’s garden. Today we will talk about theCosmos sulphureus.

Other common names: yellow cosmos 'Tango'

Family:Asteraceae

Genus:Cosmos can be annuals or perennials with simple or pinnately divided leaves and large, long-stalked daisy-like flowers in summer

Details:'Tango' is an erect, half-hardy annual, to 1.2m tall, with finely-divided mid-green leaves and semi-double flowers in shades of orange, with yellow centres, from summer into autumn

How to grow

Cultivation Grow in moderately fertile, moist but well-drained soil in full sun

PropagationPropagate by seed in mid spring

Suggested planting locations and garden types Cut Flowers Flower borders and beds Cottage & Informal Garden

How to care

PruningDeadheading should be carried out regularly to prolong flowering

PestsAphids and slugs may be a nuisance

Diseases May be affected by grey moulds

2

0