文章

Miss Chen

2018年08月19日

Lawn-grass professionals divide the United States into four main zones of grass adaptation based on climatic conditions. The Northeast region of the country falls into what's known as the cool, humid zone. Lawn grasses that do best in the Northeast are hardy, cool-season grasses that tolerate humidity in addition to cold.

Because most lawns have areas that vary in moisture as well as sun and shade exposure, a mixture of cool-season grasses normally delivers the best overall lawn. Using a mixture allows different, complementary grass types to dominate in various areas and conditions that fit them best. The major perennial lawn grasses that flourish in cool, humid Northeast conditions are:

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), which is hardy in U.S. Department of Agriculture plant hardiness zones 2 through 6. Although slow to establish from seed, Kentucky bluegrass spreads vigorously via underground stems known as rhizomes once it gets settled into sunny lawns. That spreading behavior also helps it repair itself when damaged by foot traffic or other injuries. Known for its green color and fine texture, Kentucky bluegrass flourishes in cool temperatures with the consistent soil moisture common in Northeast lawns.

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne, USDA zones 3 through 6), which establishes quickly and greens up fast in spring, making it a welcome complement to Kentucky bluegrass. Some perennial ryegrass varieties have improved longevity over older, traditional varieties and offer a finer texture that mixes well with other cool-season grasses. This versatile lawn grass tolerates sun exposure, some shade and adapts well to changing Northeast conditions, but it does not tolerate overly wet soil.

Tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea, USDA zones 4 through 7), once considered only forage pasture grass but recognized by

turf breeders for its potential as a resilient lawn grass. Fairly new varieties known as turf-type fescues retain tall fescue's clumping growth habit and its ability to thrive in poor, droughty soil. Deep-rooted, turf-type tall fescues stand up well to foot traffic and bring Northeast lawns improved texture, color and drought tolerance.

Fine fescues (Festuca spp.), such as creeping red fescue (Festuca rubra var. rubra, USDA zones 3 through 7). They excel in well-drained shade and dry areas that challenge other Northeast lawn grasses. Although these low-maintenance lawn grasses establish faster than Kentucky bluegrass, they don't tolerate the wear and tear that tall fescues can. So they work best when confined to low foot-traffic areas.

Bentgrass (Agrostis spp., USDA zones 4 through 6), historically the grass favored on golf-course greens. Newer varieties have increased the use of bentgrass by homeowners looking for dense, cushiony, golf-greenlike turf -- or a backyard putting green. Spread by above-ground stems, known as stolons, bentgrass offers a low-growth habit, fine texture and rich-green color. Bentgrass thrives in the Northeast's cool, humid climate and fertile soil.

Because most lawns have areas that vary in moisture as well as sun and shade exposure, a mixture of cool-season grasses normally delivers the best overall lawn. Using a mixture allows different, complementary grass types to dominate in various areas and conditions that fit them best. The major perennial lawn grasses that flourish in cool, humid Northeast conditions are:

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), which is hardy in U.S. Department of Agriculture plant hardiness zones 2 through 6. Although slow to establish from seed, Kentucky bluegrass spreads vigorously via underground stems known as rhizomes once it gets settled into sunny lawns. That spreading behavior also helps it repair itself when damaged by foot traffic or other injuries. Known for its green color and fine texture, Kentucky bluegrass flourishes in cool temperatures with the consistent soil moisture common in Northeast lawns.

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne, USDA zones 3 through 6), which establishes quickly and greens up fast in spring, making it a welcome complement to Kentucky bluegrass. Some perennial ryegrass varieties have improved longevity over older, traditional varieties and offer a finer texture that mixes well with other cool-season grasses. This versatile lawn grass tolerates sun exposure, some shade and adapts well to changing Northeast conditions, but it does not tolerate overly wet soil.

Tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea, USDA zones 4 through 7), once considered only forage pasture grass but recognized by

turf breeders for its potential as a resilient lawn grass. Fairly new varieties known as turf-type fescues retain tall fescue's clumping growth habit and its ability to thrive in poor, droughty soil. Deep-rooted, turf-type tall fescues stand up well to foot traffic and bring Northeast lawns improved texture, color and drought tolerance.

Fine fescues (Festuca spp.), such as creeping red fescue (Festuca rubra var. rubra, USDA zones 3 through 7). They excel in well-drained shade and dry areas that challenge other Northeast lawn grasses. Although these low-maintenance lawn grasses establish faster than Kentucky bluegrass, they don't tolerate the wear and tear that tall fescues can. So they work best when confined to low foot-traffic areas.

Bentgrass (Agrostis spp., USDA zones 4 through 6), historically the grass favored on golf-course greens. Newer varieties have increased the use of bentgrass by homeowners looking for dense, cushiony, golf-greenlike turf -- or a backyard putting green. Spread by above-ground stems, known as stolons, bentgrass offers a low-growth habit, fine texture and rich-green color. Bentgrass thrives in the Northeast's cool, humid climate and fertile soil.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年08月18日

Bleeding heart (Clerodendrum thomsoniae) prefers warm, humid conditions, making Florida's weather conditions optimal. It is hardy in United States Department of Agriculture hardiness zones 9 through 12, acting like a perennial in Central and South Florida. North Florida plants will die to the ground during frosts and freezes, but they will resprout in spring. The evergreen shrub has a vine-like habit, growing up to 15 feet tall. Bleeding heart has red and white bell-like flowers, blooming from spring through summer.

Growing Outside

Step 1

Remove weeds from a planting site located in partial shade with well-drained soil. Pull or rake the vegetation from the planting bed. If using an herbicide to kill the vegetation, do not use a product that has long-term effects to the soil, as it may kill the bleeding heart.

Step 2

Amend the planting site with peat, manure or compost, as the majority of Florida soil is sandy, lacking organic nutrients. Work the organic material into the planting area's soil to a depth of approximately 6 to 8 inches.

Step 3

Dig a hole twice as wide as the bleeding heart's root ball and as deep as it is presently growing. Place the root ball into the hole and backfill with soil. Firm the soil around the plant by patting it down with your hands.

Step 4

Install a trellis approximately 6 inches behind the bleeding heart, giving it something to grow on, if growing the plant as a vine. Push the trellis legs into the soil approximately 8 to 12 inches. Bleeding heart has a twining growth habit, instead of forming tendrils that hold onto the trellis or arbor.

Step 5

Water the bleeding heart immediately after planting, saturating the roots, and water regularly. Plants perform best in moist, well-drained soils. If your area of Florida is suffering drought conditions, water approximately three times weekly to keep the soil moist.

Step 6

Prune bleeding hearts to control their size, shape and make them bushier. If growing plants as a shrub, regular pruning will make them branch out instead of being more vine-like.

Step 7

Protect bleeding heart plants if your winter temperatures become cold, as the plants are cold tolerant to 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Cover plants with cloth coverings and water well before the frosty weather arrives.

Growing Inside Containers

Step 1

Fill a hanging basket or other container half full with a well-draining, rich, potting medium. Using containers that do not drain will cause the soil to be overly saturated and the bleeding heart will develop root rot and die.

Step 2

Remove the bleeding heart from its container and place inside the new container. Fill with soil and pack down around the plant using your hands, firming it up.

Step 3

Water the container after planting the bleeding heart, allowing water to run from the bottom. Water the plant every other day if necessary, as containerized soil dries out quickly. Stick your finger into the container's soil and if the top 1 to 2 inches are dry, apply water.

Step 4

Situate the container or hanging basket in an area that receives partial sun throughout the day.

Step 5

Bring the hanging basket or container indoors to a warm location if winter temperatures turn cold. Return the bleeding heart to its outdoor location once warm, spring weather returns.

Growing Outside

Step 1

Remove weeds from a planting site located in partial shade with well-drained soil. Pull or rake the vegetation from the planting bed. If using an herbicide to kill the vegetation, do not use a product that has long-term effects to the soil, as it may kill the bleeding heart.

Step 2

Amend the planting site with peat, manure or compost, as the majority of Florida soil is sandy, lacking organic nutrients. Work the organic material into the planting area's soil to a depth of approximately 6 to 8 inches.

Step 3

Dig a hole twice as wide as the bleeding heart's root ball and as deep as it is presently growing. Place the root ball into the hole and backfill with soil. Firm the soil around the plant by patting it down with your hands.

Step 4

Install a trellis approximately 6 inches behind the bleeding heart, giving it something to grow on, if growing the plant as a vine. Push the trellis legs into the soil approximately 8 to 12 inches. Bleeding heart has a twining growth habit, instead of forming tendrils that hold onto the trellis or arbor.

Step 5

Water the bleeding heart immediately after planting, saturating the roots, and water regularly. Plants perform best in moist, well-drained soils. If your area of Florida is suffering drought conditions, water approximately three times weekly to keep the soil moist.

Step 6

Prune bleeding hearts to control their size, shape and make them bushier. If growing plants as a shrub, regular pruning will make them branch out instead of being more vine-like.

Step 7

Protect bleeding heart plants if your winter temperatures become cold, as the plants are cold tolerant to 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Cover plants with cloth coverings and water well before the frosty weather arrives.

Growing Inside Containers

Step 1

Fill a hanging basket or other container half full with a well-draining, rich, potting medium. Using containers that do not drain will cause the soil to be overly saturated and the bleeding heart will develop root rot and die.

Step 2

Remove the bleeding heart from its container and place inside the new container. Fill with soil and pack down around the plant using your hands, firming it up.

Step 3

Water the container after planting the bleeding heart, allowing water to run from the bottom. Water the plant every other day if necessary, as containerized soil dries out quickly. Stick your finger into the container's soil and if the top 1 to 2 inches are dry, apply water.

Step 4

Situate the container or hanging basket in an area that receives partial sun throughout the day.

Step 5

Bring the hanging basket or container indoors to a warm location if winter temperatures turn cold. Return the bleeding heart to its outdoor location once warm, spring weather returns.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年08月16日

Sedum plants, also called stonecrop, require very little water to survive. The fleshy, plump leaves store water, making sedums tolerant of drought and dry, harsh conditions. All plants need water, and sedums are no exception — the trick is to water enough to keep the plants happy without watering too much. Sedum plants are easy to over water both in the ground and in containers. An over-watered sedum is likely to flop over and die more quickly than an under-watered sedum.

Step 1

Water sedums in the garden only during hot, dry weather. Press your index finger into the top 2 inches of the soil. If it is dry at the bottom, soak each plant until the ground is damp 4 inches deep.

Step 2

Allow sedums to dry out between waterings. In wet and rainy weather, do not provide sedums with additional water.

Step 3

Water potted sedums when the top 1 inch of soil dries out. Press your index finger into the soil at the edge of the pot to see how deep the moisture level is.

Step 4

Place the pot into the sink and soak it with water until it runs out of the drainage holes in the bottom of the pot. Leave the pot in the sink to drain before replacing it in its permanent location.

Step 1

Water sedums in the garden only during hot, dry weather. Press your index finger into the top 2 inches of the soil. If it is dry at the bottom, soak each plant until the ground is damp 4 inches deep.

Step 2

Allow sedums to dry out between waterings. In wet and rainy weather, do not provide sedums with additional water.

Step 3

Water potted sedums when the top 1 inch of soil dries out. Press your index finger into the soil at the edge of the pot to see how deep the moisture level is.

Step 4

Place the pot into the sink and soak it with water until it runs out of the drainage holes in the bottom of the pot. Leave the pot in the sink to drain before replacing it in its permanent location.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年08月13日

Potted mums are usually treated as annual flowers because they cannot tolerate the cold conditions during the winter months. Most potted varieties are known as florist's mums since they are sold as a living seasonal bouquet. A different mum variety, called hardy mum, is typically grown as a bedding plant. Tender, potted mums can survive the winter months with proper care and protection from frost, providing you with a second year of flowering the following fall.

Remove the mums from the pot they came in once flowering completes. Divide the roots of the separate plants. Most purchased mums come three or more plants to a pot.

Replant the mums into 6-inch diameter pots filled with standard potting soil, planting one plant per pot. Plant the mums at the same depth they were growing at in the previous pot.

Cut back the old flower stems on each mum plant. Trim the stems after the foliage begins to die back naturally.

Bring the mums indoors once the outdoor temperature drops below 60 degrees F. Place the mums in a sunny window. Leave mums outdoors in areas with warm winters.

Water the mums when the top of the soil begins to feel dry. Provide enough water to moisten the soil but avoid overwatering, which can cause soggy soil conditions.

Pinch off the top inch of each shoot once the shoots are approximately 6 inches long. Pinching causes lateral branching and further flower bud formation. Continue to pinch the plants until late July.

Move the plants outdoors once nighttime temperatures are regularly above 60 degrees F in spring. Bring the plants indoors temporarily if a late season frost is expected.

Remove the mums from the pot they came in once flowering completes. Divide the roots of the separate plants. Most purchased mums come three or more plants to a pot.

Replant the mums into 6-inch diameter pots filled with standard potting soil, planting one plant per pot. Plant the mums at the same depth they were growing at in the previous pot.

Cut back the old flower stems on each mum plant. Trim the stems after the foliage begins to die back naturally.

Bring the mums indoors once the outdoor temperature drops below 60 degrees F. Place the mums in a sunny window. Leave mums outdoors in areas with warm winters.

Water the mums when the top of the soil begins to feel dry. Provide enough water to moisten the soil but avoid overwatering, which can cause soggy soil conditions.

Pinch off the top inch of each shoot once the shoots are approximately 6 inches long. Pinching causes lateral branching and further flower bud formation. Continue to pinch the plants until late July.

Move the plants outdoors once nighttime temperatures are regularly above 60 degrees F in spring. Bring the plants indoors temporarily if a late season frost is expected.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年08月11日

Although sedums are hardy plants that grow in even harsh conditions with little care, they often become floppy and collapse in the center. Floppiness is especially a problem with tall sedum varieties such as "Autumn Joy," "Black Jack" and "Autumn Fire. A few minutes of routine maintenance keeps sedums bushy and upright.

Causes

Floppiness is normal for tall sedum varieties that aren't routinely pruned; the plant eventually becomes top heavy and collapses under the weight of the blooms. Lack of sunlight and too much fertility in the soil are also common causes of floppiness and caving in at the center of the plant. Sedum is a warm-weather succulent plant that thrives in full sunlight and average or poor soil. Some sedum varieties are tough enough to thrive in dry, gravelly soil.

Pinching

Pinching is a simple method of promoting compact, sturdy, bushy growth on new sedum plants. Pinch the growing tips of young plants when they are about 6 to 8 inches tall. Pinching causes a slight delay in blooming, but the result will be more blooms and healthier plants.

Pruning

While it seems extreme, a good pruning is the best solution for a tall, lanky sedum. If your plants are beginning to look tipsy in late spring or early summer, use your garden shears or clippers to cut the plants to a height of about 6 to 8 inches. The plants may initially look like victims of a bad haircut, but they will soon rebound and look better than ever. Pruning can safely be done every year if needed and is especially effective for sedums grown in shade.

Division

Division is the best fix for an older sedum, especially if the center of the plant looks like it's dying down and becoming woody and unattractive. To divide sedum, dig up the entire plant. Pull the plant apart into smaller plants, each with several healthy roots. If a plant is too large to dig, use a trowel or shovel to cut a section from the side of the plant. Division is a good opportunity to move the sedum to a spot in full sunlight and to discard old, woody sections. To keep sedum healthy, get in the habit of routinely dividing the plant every other year.

Tips

Water sedum sparingly; wet soil may cause sedum to rot and die. In most parts of the country, sedum thrives with no supplemental irrigation but benefits from an occasional light watering during long periods of hot, dry weather. Don't fertilize sedum; fertilizer contributes to rich soil, which can cause floppiness and weak growth.

Causes

Floppiness is normal for tall sedum varieties that aren't routinely pruned; the plant eventually becomes top heavy and collapses under the weight of the blooms. Lack of sunlight and too much fertility in the soil are also common causes of floppiness and caving in at the center of the plant. Sedum is a warm-weather succulent plant that thrives in full sunlight and average or poor soil. Some sedum varieties are tough enough to thrive in dry, gravelly soil.

Pinching

Pinching is a simple method of promoting compact, sturdy, bushy growth on new sedum plants. Pinch the growing tips of young plants when they are about 6 to 8 inches tall. Pinching causes a slight delay in blooming, but the result will be more blooms and healthier plants.

Pruning

While it seems extreme, a good pruning is the best solution for a tall, lanky sedum. If your plants are beginning to look tipsy in late spring or early summer, use your garden shears or clippers to cut the plants to a height of about 6 to 8 inches. The plants may initially look like victims of a bad haircut, but they will soon rebound and look better than ever. Pruning can safely be done every year if needed and is especially effective for sedums grown in shade.

Division

Division is the best fix for an older sedum, especially if the center of the plant looks like it's dying down and becoming woody and unattractive. To divide sedum, dig up the entire plant. Pull the plant apart into smaller plants, each with several healthy roots. If a plant is too large to dig, use a trowel or shovel to cut a section from the side of the plant. Division is a good opportunity to move the sedum to a spot in full sunlight and to discard old, woody sections. To keep sedum healthy, get in the habit of routinely dividing the plant every other year.

Tips

Water sedum sparingly; wet soil may cause sedum to rot and die. In most parts of the country, sedum thrives with no supplemental irrigation but benefits from an occasional light watering during long periods of hot, dry weather. Don't fertilize sedum; fertilizer contributes to rich soil, which can cause floppiness and weak growth.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月22日

Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) spears are the new shoots of asparagus plants that grow in spring. Asparagus grows from seed, and plants live 20 to 30 years in good growing conditions. In U.S. Department of Agriculture plant hardiness zones 4 through 8, asparagus is hardy, and plants grow 3 to 5 feet tall. Young asparagus shoots can sometimes cause skin irritation, and the red berries produced by female asparagus plants are poisonous.

Asparagus Roots

Asparagus root systems are called crowns. Asparagus growers start plants from seed and sell asparagus crowns that are one or two years old. Each crown has a central bud, and thick roots spreading out sideways. Shoots grow from the central bud.

Asparagus roots grow horizontally, not vertically. Over time, they form a wide, tuberous mat. When growing asparagus, it's important to select a growing area that can be left undisturbed for years. After planting, asparagus roots should not be moved.

Asparagus Plants

Asparagus plants develop many branched stems, which die down at the end of the growing season. Shoots develop daily on asparagus plants in spring. Newly planted crowns can produce shoots five or six weeks after planting. After a crop of young shoots is harvested, later shoots are allowed to develop so the plants can store energy for next year's crop.

As shoots grow, they produce many stems, which branch off into smaller stems. Rings of thin, hairlike structures appear on the smaller stems, which give mature asparagus plants a feathery appearance. True asparagus leaves are scalelike and tiny, and they can be seen most easily on new shoots. Asparagus stems turn yellow and wither in fall, often after the first frost.

Female and Male Asparagus

Asparagus plants are female or male. Female plants produce more stems than male plants, but the stems are thinner. Female asparagus plants also produce bright red summer berries, which contain the plant's seeds. Seeds from fallen berries can create problems the following year, when the asparagus bed becomes overrun with asparagus seedlings.

Newer varieties of asparagus are mostly male or all male plants. Male plants put all their energy into shoot production and don't waste energy on producing fruit. They also don't create problems with asparagus seedlings.

New Varieties

New asparagus varieties offer disease resistance and a range of colors. Asparagus "Jersey Knight" (Asparagus officinalis "Jersey Knight") is resistant to rust, fusarium wilt, and root and crown rot. Asparagus "Purple Passion" (Asparagus "Purple Passion") features purple spears, though these turn green when cooked. "Jersey Knight" and "Purple Passion" are hardy in USDA zones 3 through 10.

Asparagus "Jersey Giant" (Asparagus officinalis "Jersey Giant"), which is hardy in USDA zones 4 through 7, produces green spears with purple bracts. Bracts are leaflike structures. "Jersey Giant" produces two to three times more spears than some older varieties.

Asparagus Roots

Asparagus root systems are called crowns. Asparagus growers start plants from seed and sell asparagus crowns that are one or two years old. Each crown has a central bud, and thick roots spreading out sideways. Shoots grow from the central bud.

Asparagus roots grow horizontally, not vertically. Over time, they form a wide, tuberous mat. When growing asparagus, it's important to select a growing area that can be left undisturbed for years. After planting, asparagus roots should not be moved.

Asparagus Plants

Asparagus plants develop many branched stems, which die down at the end of the growing season. Shoots develop daily on asparagus plants in spring. Newly planted crowns can produce shoots five or six weeks after planting. After a crop of young shoots is harvested, later shoots are allowed to develop so the plants can store energy for next year's crop.

As shoots grow, they produce many stems, which branch off into smaller stems. Rings of thin, hairlike structures appear on the smaller stems, which give mature asparagus plants a feathery appearance. True asparagus leaves are scalelike and tiny, and they can be seen most easily on new shoots. Asparagus stems turn yellow and wither in fall, often after the first frost.

Female and Male Asparagus

Asparagus plants are female or male. Female plants produce more stems than male plants, but the stems are thinner. Female asparagus plants also produce bright red summer berries, which contain the plant's seeds. Seeds from fallen berries can create problems the following year, when the asparagus bed becomes overrun with asparagus seedlings.

Newer varieties of asparagus are mostly male or all male plants. Male plants put all their energy into shoot production and don't waste energy on producing fruit. They also don't create problems with asparagus seedlings.

New Varieties

New asparagus varieties offer disease resistance and a range of colors. Asparagus "Jersey Knight" (Asparagus officinalis "Jersey Knight") is resistant to rust, fusarium wilt, and root and crown rot. Asparagus "Purple Passion" (Asparagus "Purple Passion") features purple spears, though these turn green when cooked. "Jersey Knight" and "Purple Passion" are hardy in USDA zones 3 through 10.

Asparagus "Jersey Giant" (Asparagus officinalis "Jersey Giant"), which is hardy in USDA zones 4 through 7, produces green spears with purple bracts. Bracts are leaflike structures. "Jersey Giant" produces two to three times more spears than some older varieties.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月10日

Succulents seem custom-made for indoor gardeners. These hardy plants can thrive for long periods in poor conditions. But given proper care, succulents are some of the most beautiful plants in the world. Learn how to care for succulents plus a few varieties we love.

01How to Grow Healthy Succulents

Succulents are some of the most rewarding plants for indoor gardeners. They're tough, beautiful, and have interesting and varied foliage. Read our best tips for caring for these plants.

02Growing Aloe

Aloe is one of the most popular succulents, grown for both its beauty and health benefits.

03Growing Desert Rose (Adenium obesum)

Desert rose is a striking plant with beautiful flowers. Beware the sap, however, which can be caustic.

04Growing Sedum Morganianum (Burro's Tail)

These beautiful succulents are trailing plants that form long, striking "tails" of tear-drop shaped leaves.

05Growing Echeveria

One of the more popular varieties, Echeveria succulents grow in tight rosettes of overlapping leaves. They are perfect indoor plants: small, beautiful and easy to care for.

01How to Grow Healthy Succulents

Succulents are some of the most rewarding plants for indoor gardeners. They're tough, beautiful, and have interesting and varied foliage. Read our best tips for caring for these plants.

02Growing Aloe

Aloe is one of the most popular succulents, grown for both its beauty and health benefits.

03Growing Desert Rose (Adenium obesum)

Desert rose is a striking plant with beautiful flowers. Beware the sap, however, which can be caustic.

04Growing Sedum Morganianum (Burro's Tail)

These beautiful succulents are trailing plants that form long, striking "tails" of tear-drop shaped leaves.

05Growing Echeveria

One of the more popular varieties, Echeveria succulents grow in tight rosettes of overlapping leaves. They are perfect indoor plants: small, beautiful and easy to care for.

1

2

文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月01日

With container gardens, you can have fresh vegetables all year even when garden space is not available. Zucchini is a summer squash that grows best in full sun and warm conditions. As container culture gains popularity, many new dwarf or small growing varieties of vegetables are being developed; compact zucchini varieties are no exception, and include the culitvars Black Magic, Hybrid Jackpot, Gold Rush and Classic. Grow zucchini indoors all year round. In winter, place the pots in a south facing window where they will get the most sun.

Step 1

Fill 2-inch pots with soil-less seed starting mix. Use a pre-mixed formula available at garden centers or make your own by mixing equal parts vermiculite and peat moss. Dampen the mixture and fill the 2-inch pots.

Step 2

Place one zucchini seed in each pot and cover it with 1/2 inch of soil. Place the pots in dappled or filtered sun with a temperature range between 65 and 75 degrees Fahrenheit. Keep the soil around the seedlings damp with frequent light applications of water. The seedlings will germinate in five to seven days and be ready to transplant into a large, permanent container in three to four weeks.

Step 3

Fill one 5-gallon container for each zucchini plant. Use a well-draining soil-less potting mix and fill the pot to 1-inch below the lip of the container. Garden centers sell pre-formulated mixes for indoor vegetable container growing. Alternately, mix your own by combining equal parts loam, peat and coarse clean sand. Add a 14-14-14 liquid fertilizer to the mix. Check the back of the package to determine the correct amount.

Step 4

Dampen the potting mix with water until it is light and crumbly. Scoop out a shallow hole in the center of the pot large enough to accommodate the root ball of one zucchini plant. Select the strongest of the zucchini seedlings for planting.

Step 5

Slide the seedling out of the small pot and place it into the large container with the base of the stem planted at the same depth in the soil as it was in the seeding pot. Fill in around the roots and pat down the soil to secure the seedling in the pot. Place the potted zucchini in a sunny window where it will get at least five to six hours of sun each day.

Step 6

Fertilize once a week using a fertilizer formulated for complete nutrition. There are many combinations on the market for vegetable growing. A good, basic fertilizer formula like a 5-10-10 or a 10-10-10 fertilizer is suitable. Check the package for the correct application amount and method.

Step 7

Water when the top of the soil feels dry to the touch, usually daily or every other day for container grown zucchini plants. Soak the soil thoroughly at each watering. Place the pot on a saucer or tray to catch water and protect surfaces. Empty the saucer after every watering to prevent water from sitting around the root system.

Step 8

Harvest the zucchini plants as when they are 3 to 4 inches long and still tender. Harvest continuously as the fruits ripen to encourage the plant to keep producing. Zucchini are ready to harvest 50 to 70 days after planting.

Step 1

Fill 2-inch pots with soil-less seed starting mix. Use a pre-mixed formula available at garden centers or make your own by mixing equal parts vermiculite and peat moss. Dampen the mixture and fill the 2-inch pots.

Step 2

Place one zucchini seed in each pot and cover it with 1/2 inch of soil. Place the pots in dappled or filtered sun with a temperature range between 65 and 75 degrees Fahrenheit. Keep the soil around the seedlings damp with frequent light applications of water. The seedlings will germinate in five to seven days and be ready to transplant into a large, permanent container in three to four weeks.

Step 3

Fill one 5-gallon container for each zucchini plant. Use a well-draining soil-less potting mix and fill the pot to 1-inch below the lip of the container. Garden centers sell pre-formulated mixes for indoor vegetable container growing. Alternately, mix your own by combining equal parts loam, peat and coarse clean sand. Add a 14-14-14 liquid fertilizer to the mix. Check the back of the package to determine the correct amount.

Step 4

Dampen the potting mix with water until it is light and crumbly. Scoop out a shallow hole in the center of the pot large enough to accommodate the root ball of one zucchini plant. Select the strongest of the zucchini seedlings for planting.

Step 5

Slide the seedling out of the small pot and place it into the large container with the base of the stem planted at the same depth in the soil as it was in the seeding pot. Fill in around the roots and pat down the soil to secure the seedling in the pot. Place the potted zucchini in a sunny window where it will get at least five to six hours of sun each day.

Step 6

Fertilize once a week using a fertilizer formulated for complete nutrition. There are many combinations on the market for vegetable growing. A good, basic fertilizer formula like a 5-10-10 or a 10-10-10 fertilizer is suitable. Check the package for the correct application amount and method.

Step 7

Water when the top of the soil feels dry to the touch, usually daily or every other day for container grown zucchini plants. Soak the soil thoroughly at each watering. Place the pot on a saucer or tray to catch water and protect surfaces. Empty the saucer after every watering to prevent water from sitting around the root system.

Step 8

Harvest the zucchini plants as when they are 3 to 4 inches long and still tender. Harvest continuously as the fruits ripen to encourage the plant to keep producing. Zucchini are ready to harvest 50 to 70 days after planting.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年06月25日

There are over 10,000 succulent plants, which include cacti. Many are native to South Africa and Madagascar and the Caribbean. Succulent plants have thick, fleshy leaves, stems or roots. This is one of the ways they have adapted to dry conditions by taking advantage of whatever water is available and holding onto it for later use. When full of water, the leaves can appear swollen. When they are becoming depleted, the leaves will begin to look puckered.

Other water conserving features you may find in succulents are narrow leaves, waxy leaves, a covering of hairs or needles, reduced pores, or stomata, and ribbed leaves and stems, that can expand water holding capacity. Their functioning is fascinating, but most are also quite attractive, too. They are perfect for dry climates and periods of drought anywhere, but many are not cold hardy below USDA Zone 9. Even so, they can be grown as annuals or over-wintered indoors. Several make great houseplants. Grow them all year in containers and you can just move the whole thing in when the temperature drops.

General Succulent Care

Water: During the summer, allow the soil to dry out between waterings and then water so that the soil is soaked through, but not dripping wet. Don't let the roots sit in soggy or waterlogged soil.

In winter, most succulents will only need water every month or so. They are basically dormant. If your house is particularly dry, you may need to water more often. The leaves will pucker slightly and begin to look desiccated if they need water. But just as in the summer, don't leave the plants sitting is soggy soil.

Soil: In pots, use a chunky, fast draining soil. This is one group of plants that does not thrive in the traditional loamy garden mix. There are special potting mixes sold for succulents.

In the ground, most succulents like a slightly acidic soil pH (5.5 – 6.5). Add some organic matter to very sandy soils, to retain moisture long enough for the plants to take it up. In clay soils, raised beds are your best option.

Choosing Succulents

Below are some popular succulents that are generally easy to grow.

Other water conserving features you may find in succulents are narrow leaves, waxy leaves, a covering of hairs or needles, reduced pores, or stomata, and ribbed leaves and stems, that can expand water holding capacity. Their functioning is fascinating, but most are also quite attractive, too. They are perfect for dry climates and periods of drought anywhere, but many are not cold hardy below USDA Zone 9. Even so, they can be grown as annuals or over-wintered indoors. Several make great houseplants. Grow them all year in containers and you can just move the whole thing in when the temperature drops.

General Succulent Care

Water: During the summer, allow the soil to dry out between waterings and then water so that the soil is soaked through, but not dripping wet. Don't let the roots sit in soggy or waterlogged soil.

In winter, most succulents will only need water every month or so. They are basically dormant. If your house is particularly dry, you may need to water more often. The leaves will pucker slightly and begin to look desiccated if they need water. But just as in the summer, don't leave the plants sitting is soggy soil.

Soil: In pots, use a chunky, fast draining soil. This is one group of plants that does not thrive in the traditional loamy garden mix. There are special potting mixes sold for succulents.

In the ground, most succulents like a slightly acidic soil pH (5.5 – 6.5). Add some organic matter to very sandy soils, to retain moisture long enough for the plants to take it up. In clay soils, raised beds are your best option.

Choosing Succulents

Below are some popular succulents that are generally easy to grow.

0

1

文章

Miss Chen

2018年06月08日

Description: This perennial wildflower is highly variable in size (2-6' tall), depending on environmental conditions. The central stem branches occasionally, forming ascending lateral stems; these stems are light green, terete, and glabrous. The opposite leaves are up to 6" long and 1½" across, although they are more typically about 3" long and ½" across. They are narrowly lanceolate or oblong-lanceolate in shape, smooth (entire) along their margins, and glabrous. Upper leaf surfaces are medium to dark green, although they can become yellowish green or pale green in response to bright sunlight and hot dry conditions. The leaves are either sessile or their bases clasp the stems. Upper stems terminate in pink umbels of flowers spanning about 2-3½" across. Each flower is about ¼" across, consisting of 5 upright whitish hoods and 5 surrounding pink petals that droop downward in the manner of most milkweeds. The blooming period occurs during late summer and lasts about a month. The flowers exude a pleasant fragrance that resembles cinnamon. Afterwards, successfully cross-pollinated flowers are replaced by seedpods. The seedpods (follicles) are 3-4" long and narrowly lanceoloid-ellipsoid in shape. Immature seedpods are light green, smooth, and glabrous, turning brown at maturity. Each seedpod splits open along one side to release its seeds. These seeds have large tufts of white hair and they are distributed by the wind during the fall. The root system is rhizomatous, from which clonal colonies of plants occasionally develop.

Cultivation: The preference is full to partial sun, wet to moist conditions, and soil containing mucky clay, rich loam, or silt with rotting organic material. Occasional flooding is tolerated if it is temporary. Tolerance to hot dry conditions is poor. The leaves have a tendency to become more broad in shape in response to shady conditions.

Range & Habitat: The native Swamp Milkweed is a fairly common plant that occurs in nearly all counties of Illinois (see Distribution Map). Habitats include open to partially shaded areas in floodplain forests, swamps, thickets, moist black soil prairies, low areas along rivers and ponds, seeps and fens, marshes, and drainage ditches. Swamp Milkweed can be found in both high quality and degraded habitats.

Faunal Associations: The flowers are very popular with many kinds of insects, including bumblebees, honeybees, long-horned bees (Melissodes spp., Svastra spp.), Halictid bees, Sphecid wasps, Vespid wasps, Tiphiid wasps, Spider wasps, Mydas flies, thick-headed flies, Tachinid flies, Swallowtail butterflies, Greater Fritillaries, Monarch butterflies, and skippers. Another occasional visitor of the flowers is the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. All of these visitors seek nectar. Some insects feed destructively on the foliage and other parts of Swamp Milkweed and other Asclepias spp. (milkweeds). These insect feeders include caterpillars of the butterfly Danaus plexippes (Monarch), Labidomera clavicollis (Swamp Milkweed Leaf Beetle), Oncopeltus fasciatus (Large Milkweed Bug), and Aphis nerii (Yellow Milkweed Aphid). The latter aphid often congregates on the upper stems and young leaves (see Insect Table for other insects that feed on milkweeds). Mammalian herbivores leave this plant alone because the foliage is both bitter and toxic, containing cardiac glycosides.

Photographic Location: The photographs were taken at Meadowbrook Park in Urbana, Illinois, and at Weaver Park of the same city.

Comments: This is usually an attractive and elegant plant. It is almost the only milkweed in Illinois that favors wetland habitats. Swamp Milkweed is easily distinguished from other milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) by its erect umbels of pink flowers, tall branching habit, and relatively narrow leaves. Other milkweeds with pink flowers, such as Asclepias syriaca (Common Milkweed) and Asclepias sullivantii (Prairie Milkweed), are shorter and less branched plants with wider leaves. Sometimes stray plants of Swamp Milkweed occur in drier areas; these specimens are usually much shorter and little branched, but their leaves remain narrow in shape.

Cultivation: The preference is full to partial sun, wet to moist conditions, and soil containing mucky clay, rich loam, or silt with rotting organic material. Occasional flooding is tolerated if it is temporary. Tolerance to hot dry conditions is poor. The leaves have a tendency to become more broad in shape in response to shady conditions.

Range & Habitat: The native Swamp Milkweed is a fairly common plant that occurs in nearly all counties of Illinois (see Distribution Map). Habitats include open to partially shaded areas in floodplain forests, swamps, thickets, moist black soil prairies, low areas along rivers and ponds, seeps and fens, marshes, and drainage ditches. Swamp Milkweed can be found in both high quality and degraded habitats.

Faunal Associations: The flowers are very popular with many kinds of insects, including bumblebees, honeybees, long-horned bees (Melissodes spp., Svastra spp.), Halictid bees, Sphecid wasps, Vespid wasps, Tiphiid wasps, Spider wasps, Mydas flies, thick-headed flies, Tachinid flies, Swallowtail butterflies, Greater Fritillaries, Monarch butterflies, and skippers. Another occasional visitor of the flowers is the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. All of these visitors seek nectar. Some insects feed destructively on the foliage and other parts of Swamp Milkweed and other Asclepias spp. (milkweeds). These insect feeders include caterpillars of the butterfly Danaus plexippes (Monarch), Labidomera clavicollis (Swamp Milkweed Leaf Beetle), Oncopeltus fasciatus (Large Milkweed Bug), and Aphis nerii (Yellow Milkweed Aphid). The latter aphid often congregates on the upper stems and young leaves (see Insect Table for other insects that feed on milkweeds). Mammalian herbivores leave this plant alone because the foliage is both bitter and toxic, containing cardiac glycosides.

Photographic Location: The photographs were taken at Meadowbrook Park in Urbana, Illinois, and at Weaver Park of the same city.

Comments: This is usually an attractive and elegant plant. It is almost the only milkweed in Illinois that favors wetland habitats. Swamp Milkweed is easily distinguished from other milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) by its erect umbels of pink flowers, tall branching habit, and relatively narrow leaves. Other milkweeds with pink flowers, such as Asclepias syriaca (Common Milkweed) and Asclepias sullivantii (Prairie Milkweed), are shorter and less branched plants with wider leaves. Sometimes stray plants of Swamp Milkweed occur in drier areas; these specimens are usually much shorter and little branched, but their leaves remain narrow in shape.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年05月14日

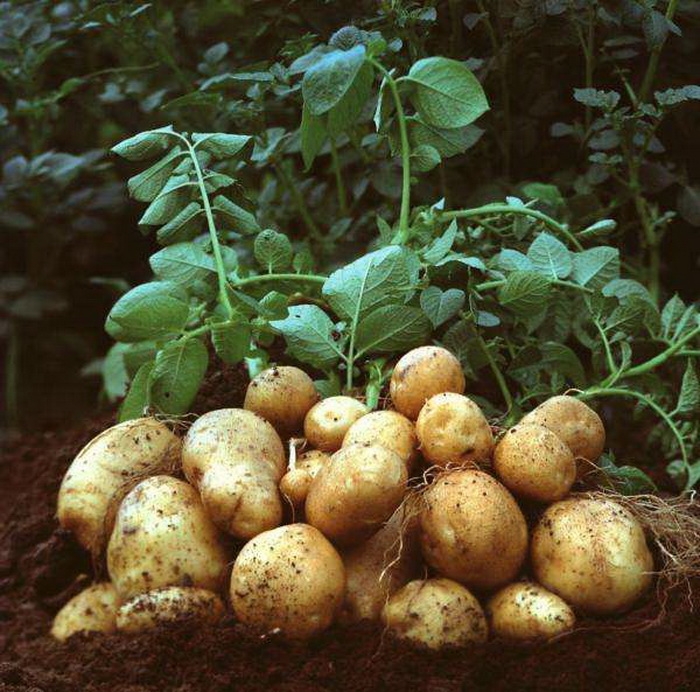

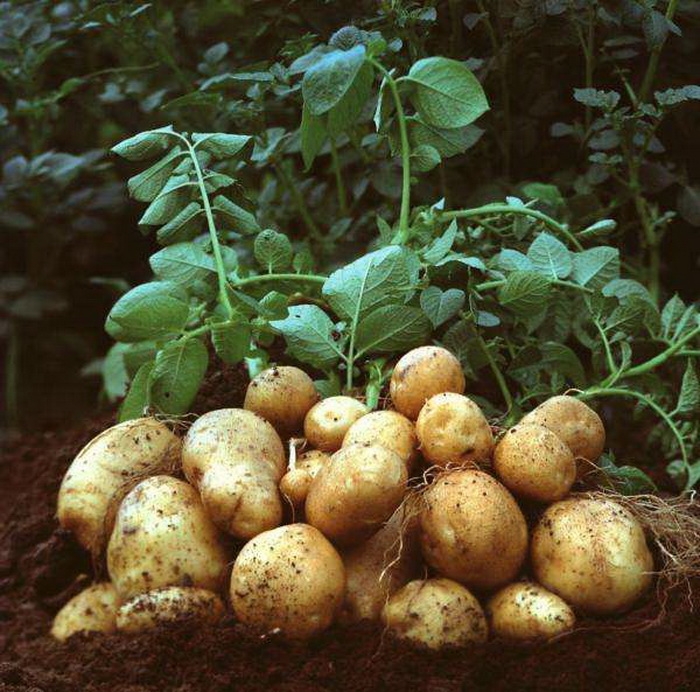

Potatoes are easy to grow, and the plants can be highly productive if grown under the best conditions. Oklahoma gardeners are fortunate to have a climate well-suited to growing potatoes, and starting your plants at the right time will help make sure your crop is a bountiful one.

Time Frame

Potatoes are considered cool-season vegetables. They are not particularly sensitive to frost, and can be planted earlier than more tender garden plants. You can plant potatoes from mid-February to mid-March. If you live in southern Oklahoma, you should plant during the earlier portion of this range.

Considerations

Potatoes grow best in soil that is well aerated, moist and well drained; avoid compacting the soil. A pH between 5.0 and 5.5 is ideal. Potatoes grow well in sunny conditions, but excessive heat and lack of moisture reduce yield.

Sweet Potatoes

Sweet potatoes are less hardy than regular potatoes, and should be planted between May 1 and June 20.

Time Frame

Potatoes are considered cool-season vegetables. They are not particularly sensitive to frost, and can be planted earlier than more tender garden plants. You can plant potatoes from mid-February to mid-March. If you live in southern Oklahoma, you should plant during the earlier portion of this range.

Considerations

Potatoes grow best in soil that is well aerated, moist and well drained; avoid compacting the soil. A pH between 5.0 and 5.5 is ideal. Potatoes grow well in sunny conditions, but excessive heat and lack of moisture reduce yield.

Sweet Potatoes

Sweet potatoes are less hardy than regular potatoes, and should be planted between May 1 and June 20.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年04月28日

Dozens of bell pepper varieties in an array of colors can be grown in your home vegetable garden each summer. Bell peppers can can grow in all U.S. Department of Agriculture hardiness zones and tolerate a variety of climatic conditions. However, because they are a warm-season vegetable, they do best with a long growing season, the Iowa State University Extension reports. Regular applications of fertilizer can benefit the plants, bettering your odds for a healthy harvest.

Before Planting

Pre-treat the soil where you will plant bell peppers with a 5-10-5 fertilizer. Apply 2 to 3 pounds for every 100 square feet of garden space, the Iowa State University Extension advises. Alternately, have your soil tested prior to planting to see what specific needs your soil has and whether it would benefit from a different fertilizer.

After Transplanting

Once you transplant pepper plants outdoors, treat them with water-soluble fertilizer. The Iowa extension recommends using a water-soluble fertilizer or making your own solution by mixing 2 tbsp. of a 10-10-10 fertilizer in 1 gallon of water. Each plant should receive between 1 and 2 cups of the fertilizer.

After Fruiting

As your bell peppers grow, they will need at least one more fertilizer application. Wait until the plants set their first young peppers before applying fertilizer, the University of Illinois Extension reports. Use the same fertilizer you applied after the plants were set in the soil and repeat every three or four weeks. Always follow manufacturer's directions carefully to ensure you don't apply too much.

Application Technique

When fertilizing bell peppers and many other garden vegetables, side-dress the plants to prevent damage to the stems and leaves. To do this, apply fertilizer to the soil several inches away from the plant stem, Fort Valley State University recommends. Water the plants thoroughly afterwards, so the fertilizer incorporates into the soil.

Before Planting

Pre-treat the soil where you will plant bell peppers with a 5-10-5 fertilizer. Apply 2 to 3 pounds for every 100 square feet of garden space, the Iowa State University Extension advises. Alternately, have your soil tested prior to planting to see what specific needs your soil has and whether it would benefit from a different fertilizer.

After Transplanting

Once you transplant pepper plants outdoors, treat them with water-soluble fertilizer. The Iowa extension recommends using a water-soluble fertilizer or making your own solution by mixing 2 tbsp. of a 10-10-10 fertilizer in 1 gallon of water. Each plant should receive between 1 and 2 cups of the fertilizer.

After Fruiting

As your bell peppers grow, they will need at least one more fertilizer application. Wait until the plants set their first young peppers before applying fertilizer, the University of Illinois Extension reports. Use the same fertilizer you applied after the plants were set in the soil and repeat every three or four weeks. Always follow manufacturer's directions carefully to ensure you don't apply too much.

Application Technique

When fertilizing bell peppers and many other garden vegetables, side-dress the plants to prevent damage to the stems and leaves. To do this, apply fertilizer to the soil several inches away from the plant stem, Fort Valley State University recommends. Water the plants thoroughly afterwards, so the fertilizer incorporates into the soil.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年04月18日

Cucumbers are one of the less finicky producers in a summer garden. With the right conditions, they tend to grow rather quickly and will be ripe and ready to eat within six weeks. Obtaining the right conditions for a long cuke over a stunted, rounded or crumpled one isn't that difficult if you pay attention to the details.

Know the Type of Cucumber You're Getting

You can choose vining cucumbers, perfect for container gardening or small gardens, or bush cucumbers. A vining cucumber loves a trellis to hold onto as it searches for higher ground with tiny tendrils. These are easier to pick and can be more prolific in their production than the bush variety. There are three main types to choose from: pickling, burpless (a less bitter variety) and slicing. Choose one that works best with your temperature and sun exposure. Your local gardening group or collective will be able to tell you the exact best cucumber to grow in your area and may also hook you up with the proper fertilizer to get them growing long and green rather than stout, spotted and curled. Some cucumbers were bred to be different, round or bulbous, such as the lemon cucumber, which looks like a tennis ball with stripes. Know what to expect when you choose your cucumber so you don't panic if it leans more toward yellow, such as the tasty Chinese yellow cucumber.

Why Cucumbers Become Round

If you notice your cucumber becoming misshapen before it's ready to pick, there are a few ways to remedy the situation. Cucumbers need a lot of water, as well as good drainage, to keep them perky and perfectly formed over the weeks of growing. If you notice your cucumbers beginning to bend, check your fertilizer. A good rule for a fertilizer is a 10-7-7 mix of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Ensure that they aren't struggling to find sun exposure. If they have to work to get at least six hours of full sun, they may get weak and have a hard time producing. If the temperatures get to boiling, it can kill pollen and keep your crop from getting proper pollination. You can take a small paint brush and spread the pollen from bloom to bloom to give your plant a boost.

How to Grow Great Cucumbers

You can start cucumbers by seed indoors three to four weeks before you plan to put them in the ground. Once the soil is above 70 degrees Fahrenheit, you can transplant your seedlings or put seeds straight in the ground. Don't crowd your cukes. Plant seeds 36 inches apart at least as they like to spread their umbrella-like leaves. Vines can be placed a foot apart if they have a trellis to lean on.

Cucumbers love it loose, so don't pack them into tight spots with hard soil. A nice, light sandy soil is preferred. A good mix of compost worked into the top two inches of the soil before planting will make the soil a happy home for cucumbers. If you have clay soil, you can add peat or compost to make it more hospitable. Add more compost to your soil after new shoots appear, about a month after initial planting.

Make sure the area you plant in has good drainage because cucumbers do not like to get their feet wet and are susceptible to root rot if left in standing water for too long.

Know the Type of Cucumber You're Getting

You can choose vining cucumbers, perfect for container gardening or small gardens, or bush cucumbers. A vining cucumber loves a trellis to hold onto as it searches for higher ground with tiny tendrils. These are easier to pick and can be more prolific in their production than the bush variety. There are three main types to choose from: pickling, burpless (a less bitter variety) and slicing. Choose one that works best with your temperature and sun exposure. Your local gardening group or collective will be able to tell you the exact best cucumber to grow in your area and may also hook you up with the proper fertilizer to get them growing long and green rather than stout, spotted and curled. Some cucumbers were bred to be different, round or bulbous, such as the lemon cucumber, which looks like a tennis ball with stripes. Know what to expect when you choose your cucumber so you don't panic if it leans more toward yellow, such as the tasty Chinese yellow cucumber.

Why Cucumbers Become Round

If you notice your cucumber becoming misshapen before it's ready to pick, there are a few ways to remedy the situation. Cucumbers need a lot of water, as well as good drainage, to keep them perky and perfectly formed over the weeks of growing. If you notice your cucumbers beginning to bend, check your fertilizer. A good rule for a fertilizer is a 10-7-7 mix of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Ensure that they aren't struggling to find sun exposure. If they have to work to get at least six hours of full sun, they may get weak and have a hard time producing. If the temperatures get to boiling, it can kill pollen and keep your crop from getting proper pollination. You can take a small paint brush and spread the pollen from bloom to bloom to give your plant a boost.

How to Grow Great Cucumbers

You can start cucumbers by seed indoors three to four weeks before you plan to put them in the ground. Once the soil is above 70 degrees Fahrenheit, you can transplant your seedlings or put seeds straight in the ground. Don't crowd your cukes. Plant seeds 36 inches apart at least as they like to spread their umbrella-like leaves. Vines can be placed a foot apart if they have a trellis to lean on.

Cucumbers love it loose, so don't pack them into tight spots with hard soil. A nice, light sandy soil is preferred. A good mix of compost worked into the top two inches of the soil before planting will make the soil a happy home for cucumbers. If you have clay soil, you can add peat or compost to make it more hospitable. Add more compost to your soil after new shoots appear, about a month after initial planting.

Make sure the area you plant in has good drainage because cucumbers do not like to get their feet wet and are susceptible to root rot if left in standing water for too long.

1

1

文章

Miss Chen

2018年04月16日

Soybeans (Glycine max) are a common annual farm crop produced for the oil market, as well as livestock feed and human consumption. The warm-weather legume grows under a variety of climate conditions, and many new hybrids offer shorter maturity dates, allowing northern farmers more options for growing soybeans. Soybeans should not be planted until the soil temperature is at least 60 degrees Fahrenheit and prefer average daytime temperatures in the 70s.

Maturity Dates and Varieties

Different varieties of soybeans mature at different rates. This is often stated in seed packets as a number of days and reflects the estimated time between planting and crop maturity. Many soybean varieties have maturity dates ranging between 90 and 150 days, with some hybrids developed for northern regions maturing even faster. Select a variety suited for your local climate and its number of anticipated growing days.

Late Planting

Soybeans respond to the shortening days in the fall by accelerating the seed-maturing process. This means delayed planting may still lead to a harvestable crop in the fall. Purdue University estimates that for each three days spring planting is delayed, harvest is delayed one day. The acceleration of the maturity may lead to a smaller yield because the plant may set fewer pods.

Plant Emergence

It commonly takes a soybean seed about two days to germinate and sprout. The new plant doesn't emerge from the ground until about one week after planting. Plants are at the most vulnerable during this process and can be damaged by low temperatures or pests. If the initial planting is lost, the crop can sometimes be replanted with a shorter-maturing variety.

Harvest

The best time to harvest soybeans is when the seeds are fully developed but the pod has not yet turned from green to yellow. Most commercial varieties of soybeans hold in this window of development for about a week before the pod starts to dry. Once the pod dries, it is likely to shatter during harvest, leading to seed loss. Harvest dates are determined by the crop conditions, since the maturity rate is affected by temperature and humidity levels. For example, a 100-day soybean may take 110 days from planting to maturity if conditions are cooler and wetter than normal.

Maturity Dates and Varieties

Different varieties of soybeans mature at different rates. This is often stated in seed packets as a number of days and reflects the estimated time between planting and crop maturity. Many soybean varieties have maturity dates ranging between 90 and 150 days, with some hybrids developed for northern regions maturing even faster. Select a variety suited for your local climate and its number of anticipated growing days.

Late Planting

Soybeans respond to the shortening days in the fall by accelerating the seed-maturing process. This means delayed planting may still lead to a harvestable crop in the fall. Purdue University estimates that for each three days spring planting is delayed, harvest is delayed one day. The acceleration of the maturity may lead to a smaller yield because the plant may set fewer pods.

Plant Emergence

It commonly takes a soybean seed about two days to germinate and sprout. The new plant doesn't emerge from the ground until about one week after planting. Plants are at the most vulnerable during this process and can be damaged by low temperatures or pests. If the initial planting is lost, the crop can sometimes be replanted with a shorter-maturing variety.

Harvest

The best time to harvest soybeans is when the seeds are fully developed but the pod has not yet turned from green to yellow. Most commercial varieties of soybeans hold in this window of development for about a week before the pod starts to dry. Once the pod dries, it is likely to shatter during harvest, leading to seed loss. Harvest dates are determined by the crop conditions, since the maturity rate is affected by temperature and humidity levels. For example, a 100-day soybean may take 110 days from planting to maturity if conditions are cooler and wetter than normal.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年04月15日

Okra seeds need optimal conditions to germinate. The seed coat is thick and hard, inhibiting germination unless the seeds are treated to enhance germination. Some seeds are scarified with acid by the seed producer to increase germination rates. Check the package expiration date, old seeds are less likely to germinate. Under ideal conditions, your okra should germinate within seven days.

Conditions that Encourage Sprouting

Okra grows best in well-drained soils with a pH between 6.5 to 7.5. It is a hot-weather crop that prefers full sun. Sow the seeds directly into the garden or plant them in peat pots for later transplanting. Plant the seeds 3/4 to 1 inch deep in hills 12 to 24 inches apart. Plant two seeds per hole and thin the plants, leaving the strongest plant when they reach approximately 3 inches tall.

Soak the Seeds For Better Germination

Iowa State University Extension recommends soaking the seeds overnight before planting to soften the seed coat and increase the germination rate. Soaking for four to six hours will do the job. Either cover the seeds in water or wrap them in damp paper towels.

Freeze the Seeds for Better Germination

Another way to increase the chances of germination is to freeze the seeds before planting, according to the Clemson University Extension. Freezing breaks the seed coat and increases potential germination. Place the seeds in the freezer overnight before planting in warm soil.

Temperatures for Germination

Okra sprouts best in warm soil. Plant it in the spring or early summer when the soil temperature has reached at least 70 degrees F and the daytime temperatures are reaching 75 to 90 degrees. Okra seeds do not sprout in soil temperatures below 65 degrees.

Days to Maturity

Viable okra seeds germinate within seven days and then require approximately 48 to 75 days to maturity, depending on the variety. The plants and pods grow very fast and require picking every day or two to prevent the pods from becoming large and fibrous.

Conditions that Encourage Sprouting

Okra grows best in well-drained soils with a pH between 6.5 to 7.5. It is a hot-weather crop that prefers full sun. Sow the seeds directly into the garden or plant them in peat pots for later transplanting. Plant the seeds 3/4 to 1 inch deep in hills 12 to 24 inches apart. Plant two seeds per hole and thin the plants, leaving the strongest plant when they reach approximately 3 inches tall.

Soak the Seeds For Better Germination

Iowa State University Extension recommends soaking the seeds overnight before planting to soften the seed coat and increase the germination rate. Soaking for four to six hours will do the job. Either cover the seeds in water or wrap them in damp paper towels.

Freeze the Seeds for Better Germination

Another way to increase the chances of germination is to freeze the seeds before planting, according to the Clemson University Extension. Freezing breaks the seed coat and increases potential germination. Place the seeds in the freezer overnight before planting in warm soil.

Temperatures for Germination

Okra sprouts best in warm soil. Plant it in the spring or early summer when the soil temperature has reached at least 70 degrees F and the daytime temperatures are reaching 75 to 90 degrees. Okra seeds do not sprout in soil temperatures below 65 degrees.

Days to Maturity

Viable okra seeds germinate within seven days and then require approximately 48 to 75 days to maturity, depending on the variety. The plants and pods grow very fast and require picking every day or two to prevent the pods from becoming large and fibrous.

0

0