文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月24日

Description: This herbaceous perennial plant is 2-6' tall and unbranched, except sometimes toward the apex, where the flowers occur. The central stem is relative stout, pale green, terete, and usually short-pubescent (less often glabrous). The opposite leaves are up to 8" long and 3½" wide, broadly oblong in shape, and smooth along their margins. The upper leaf surface is pale-medium to dark green and hairless above, while the lower leaf surface is densely covered with woolly hairs that are very short. There is a prominent central vein along the length of each leaf, and finer side veins that radiate outward toward the smooth margins. When either the central stem or leaves are torn, a milky sap oozes out that has variable toxicity in the form of cardiac glycosides.

Umbels of flowers, each about 2½-4" across, emerge from the axils of the upper leaves. These flowers are quite fragrant, with a scent resembling violets or pansies, and they range in color from faded light pink to reddish purple. Each flower is about ¼" across, consisting of 5 reflexed petals and 5 raised hoods with curved horns. The hoods are more light-colored than the petals. The pedicels of the flowers are light green to pale red and hairy. The blooming period lasts about 1-1½ months from early to mid-summer. The seedpods (follicles) are 3-4" long, broadly lanceoloid, and covered with soft prickles and short woolly hairs. At maturity, each seedpod split along one side to release numerous seeds that have large tufts of white hair. Dispersion of seed is by wind. The root system has long creeping rhizomes, promoting the vegetative spread of this plant.

Cultivation: The preference is full sun, rich loamy soil, and mesic conditions, but this robust plant can tolerate a variety of situations, including partial sun and a high clay or sand content in the soil. Under ideal conditions, Common Milkweed can become 6' tall and spread aggressively, but it is more typically about 3-4' tall. This plant is very easy to grow once it becomes established.

Range & Habitat: The native Common Milkweed occurs in every county of Illinois and it is quite common (see Distribution Map). Habitats include moist to dry black soil prairies, sand prairies, sand dunes along lake shores, thickets, woodland borders, fields and pastures, abandoned fields, vacant lots, fence rows, and areas along railroads and roadsides. This plant is a colonizer of disturbed areas in both natural and developed habitats.

Faunal Associations: The flowers are very popular with many kinds of insects, especially long-tongued bees, wasps, flies, skippers, and butterflies, which seek nectar. Other insect visitors include short-tongued bees, various milkweed plant bugs, and moths, including Sphinx moths. Among these, the larger butterflies, predatory wasps, and long-tongued bees are more likely to remove the pollinia from the flowers. Some of the smaller insects can have their legs entrapped by the flowers and die. Common Milkweed doesn't produce fertile seeds without cross-pollination. The caterpillars of Danaus plexippes (Monarch Butterfly) feed on the foliage, as do the caterpillars of a few moths, including Enchaetes egle (Milkweed Tiger Moth), Cycnia inopinatus (Unexpected Cycnia), and Cycnia tenera (Delicate Cycnia). Less common insects feeding on this plant include Neacoryphus bicrucis (Seed Bug sp.) and Gymnetron tetrum (Weevil sp.); see Insect Table for other insect feeders). Many of these insects are brightly colored – a warning to potential predators of the toxicity that they acquired from feeding on milkweed. Mammalian herbivores don't eat this plant because of the bitterness of the leaves and their toxic properties.

Photographic Location: The photographs were taken at Meadowbrook Park in Urbana, Illinois, and along a roadside ditch in Champaign, Illinois.

Comments: Depending on the local ecotype, Common Milkweed is highly variable in appearance. The color of the flowers may be highly attractive, or faded and dingy-looking. This plant is often regarded as a weed to be destroyed, but its flowers and foliage provide food for many kinds of insects. Common Milkweed can be distinguished from other milkweeds by its prickly follicles (seedpods) – other Asclepias spp. within Illinois have follicles that are smooth, or nearly so.

Umbels of flowers, each about 2½-4" across, emerge from the axils of the upper leaves. These flowers are quite fragrant, with a scent resembling violets or pansies, and they range in color from faded light pink to reddish purple. Each flower is about ¼" across, consisting of 5 reflexed petals and 5 raised hoods with curved horns. The hoods are more light-colored than the petals. The pedicels of the flowers are light green to pale red and hairy. The blooming period lasts about 1-1½ months from early to mid-summer. The seedpods (follicles) are 3-4" long, broadly lanceoloid, and covered with soft prickles and short woolly hairs. At maturity, each seedpod split along one side to release numerous seeds that have large tufts of white hair. Dispersion of seed is by wind. The root system has long creeping rhizomes, promoting the vegetative spread of this plant.

Cultivation: The preference is full sun, rich loamy soil, and mesic conditions, but this robust plant can tolerate a variety of situations, including partial sun and a high clay or sand content in the soil. Under ideal conditions, Common Milkweed can become 6' tall and spread aggressively, but it is more typically about 3-4' tall. This plant is very easy to grow once it becomes established.

Range & Habitat: The native Common Milkweed occurs in every county of Illinois and it is quite common (see Distribution Map). Habitats include moist to dry black soil prairies, sand prairies, sand dunes along lake shores, thickets, woodland borders, fields and pastures, abandoned fields, vacant lots, fence rows, and areas along railroads and roadsides. This plant is a colonizer of disturbed areas in both natural and developed habitats.

Faunal Associations: The flowers are very popular with many kinds of insects, especially long-tongued bees, wasps, flies, skippers, and butterflies, which seek nectar. Other insect visitors include short-tongued bees, various milkweed plant bugs, and moths, including Sphinx moths. Among these, the larger butterflies, predatory wasps, and long-tongued bees are more likely to remove the pollinia from the flowers. Some of the smaller insects can have their legs entrapped by the flowers and die. Common Milkweed doesn't produce fertile seeds without cross-pollination. The caterpillars of Danaus plexippes (Monarch Butterfly) feed on the foliage, as do the caterpillars of a few moths, including Enchaetes egle (Milkweed Tiger Moth), Cycnia inopinatus (Unexpected Cycnia), and Cycnia tenera (Delicate Cycnia). Less common insects feeding on this plant include Neacoryphus bicrucis (Seed Bug sp.) and Gymnetron tetrum (Weevil sp.); see Insect Table for other insect feeders). Many of these insects are brightly colored – a warning to potential predators of the toxicity that they acquired from feeding on milkweed. Mammalian herbivores don't eat this plant because of the bitterness of the leaves and their toxic properties.

Photographic Location: The photographs were taken at Meadowbrook Park in Urbana, Illinois, and along a roadside ditch in Champaign, Illinois.

Comments: Depending on the local ecotype, Common Milkweed is highly variable in appearance. The color of the flowers may be highly attractive, or faded and dingy-looking. This plant is often regarded as a weed to be destroyed, but its flowers and foliage provide food for many kinds of insects. Common Milkweed can be distinguished from other milkweeds by its prickly follicles (seedpods) – other Asclepias spp. within Illinois have follicles that are smooth, or nearly so.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月14日

Eggplants (Solanum melongena) do not have a male or female gender, but they are endowed with cross-pollinating male and female flowers on each plant. We tend to think of the eggplant as a vegetable, but like the tomato, it is classified as a fruit. Fruit or veggie, eggplants do not have a gender.

Dimple Differences

Two types of eggplant may develop on one plant, and that is likely the reason the myth of gender got started. One type has a roundish dimpled area at the blossom end, and the other type has a more oval-shaped dimpled area. The oval-dimpled eggplants are said to have more seeds and be less meaty than the roundish dimpled eggplants. Agriculture experts at the University of Illinois Extension describe the differences as a product of reproduction, not differences of gender.

Good Things About Eggplants

Eggplants love hot weather and grow well where more tender, leafy vegetables may wilt. They like growing conditions similar to tomatoes; they are from the same nightshade family of plants. Eggplants thrive in direct sunlight for six to eight hours per day.

There are several to grow , including egg-shaped 'Black Bell' and the long, slender variety called 'Ichiban.' The dimple differences can appear on fruit from every variety.

Easy To Grow

Once you have found the warm spot in the garden to grow your eggplants, start seeds or seedlings when nighttime temperatures are consistently at or above 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Their root systems are subject to cold damage and do not recover easily once they are affected. Allow 2 to 3 feet of growing space between plants. Give eggplant a steady supply of moisture but not enough to create soggy soil conditions. Test for dryness by inserting your finger in the soil; it should feel moist up to the first joint. A soaker hose or drip system is ideal for giving a slow, steady supply of moisture.

Harvest Time and the Dimples

Eggplants bloom with violet flowers in mid- to late summer, and small fruit begin to develop. The time from seed germination to harvest is 16 to 24 weeks, depending on the variety and growing conditions. Plants with a heavy load of fruit may fall over and need to be staked or propped up with a small tomato cage.

Eggplants are ready to pick when their skin is bright and glossy. If they are dull colored, the fruit has been left too long on the plant and may be bitter. Now is the time to turn the fruit upside down, see whether you have a round-dimpled eggplant or an oval-dimpled eggplant, and begin the enjoyment of and eating your eggplant.

Dimple Differences

Two types of eggplant may develop on one plant, and that is likely the reason the myth of gender got started. One type has a roundish dimpled area at the blossom end, and the other type has a more oval-shaped dimpled area. The oval-dimpled eggplants are said to have more seeds and be less meaty than the roundish dimpled eggplants. Agriculture experts at the University of Illinois Extension describe the differences as a product of reproduction, not differences of gender.

Good Things About Eggplants

Eggplants love hot weather and grow well where more tender, leafy vegetables may wilt. They like growing conditions similar to tomatoes; they are from the same nightshade family of plants. Eggplants thrive in direct sunlight for six to eight hours per day.

There are several to grow , including egg-shaped 'Black Bell' and the long, slender variety called 'Ichiban.' The dimple differences can appear on fruit from every variety.

Easy To Grow

Once you have found the warm spot in the garden to grow your eggplants, start seeds or seedlings when nighttime temperatures are consistently at or above 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Their root systems are subject to cold damage and do not recover easily once they are affected. Allow 2 to 3 feet of growing space between plants. Give eggplant a steady supply of moisture but not enough to create soggy soil conditions. Test for dryness by inserting your finger in the soil; it should feel moist up to the first joint. A soaker hose or drip system is ideal for giving a slow, steady supply of moisture.

Harvest Time and the Dimples

Eggplants bloom with violet flowers in mid- to late summer, and small fruit begin to develop. The time from seed germination to harvest is 16 to 24 weeks, depending on the variety and growing conditions. Plants with a heavy load of fruit may fall over and need to be staked or propped up with a small tomato cage.

Eggplants are ready to pick when their skin is bright and glossy. If they are dull colored, the fruit has been left too long on the plant and may be bitter. Now is the time to turn the fruit upside down, see whether you have a round-dimpled eggplant or an oval-dimpled eggplant, and begin the enjoyment of and eating your eggplant.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月13日

Cabbages produce seeds from flowers but you don't usually see them do it because it takes more than a year. If you want to get your own seed from your cabbages, choose open-pollinated varieties rather than F1 hybrids, so they'll breed true. Cabbages cross easily, not only with other cabbages but with kale, kohlrabi, cauliflower, broccoli, collards and Brussels sprouts, so you'll need to protect your seed cabbages if other plants of the same species are blooming within 1,000 feet.

Step 1

Plant your cabbage to mature as late in the fall as practical. Choose the best dozen heads to use for seed. If your winters are mild, rarely getting more than a few degrees below freezing, cover the heads with straw or other loose mulch to protect them from freezing. If your winters are severe, pull them up with roots intact and store them in a root cellar or bury them under at least a foot of dirt and mulch, deeper in the coldest climates. You want them to be kept cool but never frozen solid and damp enough so they don't dry out but not so damp that they mold.

Step 2

Dig up or uncover the cabbage heads when the danger of hard freezing is past. Plant or transplant them 1/12 to 2 feet apart, spaced in a square or grid rather than a row if you'll need to protect them from cross-pollination. Plant them deep so the heads are at ground level. Cut an "x" in the top of each head, about an inch deep, to let the flowering stock emerge easily.

Step 3

Set poles upright around the cabbages about 4 feet high and connect the tops with wire or heavy cord. When the seed stalks emerge in early summer but before they bloom, cover the framework with netting that's woven tightly enough that bees can't get through. When the flowers open, raise the cover long enough each morning to allow bees to enter and let them stay inside to pollinate the plants, then raise the cover to release them. Repeat while the plants are blooming, then remove the covering while the seeds mature. If no other plants that cross with cabbages are blooming at the same time within 1,000 feet, you can omit the protection and just let bees come and go to pollinate them naturally.

Step 4

Tie the seed stalks loosely to poles to keep them from bending or breaking in strong wind or rain as the seeds mature. Wait several weeks for the seeds to ripen.

Step 5

Pick the seedpods when they first turn brown, before they burst open and spill their seeds. Some mature before others, so pick them every few days. Lay them on a tray in the sun to finish drying. If you don't mind losing some, you can wait until the majority have turned brown, cut the whole seed stalk and lay it on a tray or sheet to dry. For the most viable seed, let the pods mature as long as possible on the plant.

Step 6

Put the pods in a cloth bag and lightly pound it or crush it to knock the seeds loose, then carefully pour them out. Use a coarse sieve to separate them from larger debris or pour them from one container to another in a light breeze to let the lighter pieces of broken pod blow away. Keep the seeds in a dark, dry place until you want to plant them. They should keep several years.

Step 1

Plant your cabbage to mature as late in the fall as practical. Choose the best dozen heads to use for seed. If your winters are mild, rarely getting more than a few degrees below freezing, cover the heads with straw or other loose mulch to protect them from freezing. If your winters are severe, pull them up with roots intact and store them in a root cellar or bury them under at least a foot of dirt and mulch, deeper in the coldest climates. You want them to be kept cool but never frozen solid and damp enough so they don't dry out but not so damp that they mold.

Step 2

Dig up or uncover the cabbage heads when the danger of hard freezing is past. Plant or transplant them 1/12 to 2 feet apart, spaced in a square or grid rather than a row if you'll need to protect them from cross-pollination. Plant them deep so the heads are at ground level. Cut an "x" in the top of each head, about an inch deep, to let the flowering stock emerge easily.

Step 3

Set poles upright around the cabbages about 4 feet high and connect the tops with wire or heavy cord. When the seed stalks emerge in early summer but before they bloom, cover the framework with netting that's woven tightly enough that bees can't get through. When the flowers open, raise the cover long enough each morning to allow bees to enter and let them stay inside to pollinate the plants, then raise the cover to release them. Repeat while the plants are blooming, then remove the covering while the seeds mature. If no other plants that cross with cabbages are blooming at the same time within 1,000 feet, you can omit the protection and just let bees come and go to pollinate them naturally.

Step 4

Tie the seed stalks loosely to poles to keep them from bending or breaking in strong wind or rain as the seeds mature. Wait several weeks for the seeds to ripen.

Step 5

Pick the seedpods when they first turn brown, before they burst open and spill their seeds. Some mature before others, so pick them every few days. Lay them on a tray in the sun to finish drying. If you don't mind losing some, you can wait until the majority have turned brown, cut the whole seed stalk and lay it on a tray or sheet to dry. For the most viable seed, let the pods mature as long as possible on the plant.

Step 6

Put the pods in a cloth bag and lightly pound it or crush it to knock the seeds loose, then carefully pour them out. Use a coarse sieve to separate them from larger debris or pour them from one container to another in a light breeze to let the lighter pieces of broken pod blow away. Keep the seeds in a dark, dry place until you want to plant them. They should keep several years.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月11日

Description: This herbaceous perennial plant is 2-6' tall and unbranched, except sometimes toward the apex, where the flowers occur. The central stem is relative stout, pale green, terete, and usually short-pubescent (less often glabrous). The opposite leaves are up to 8" long and 3½" wide, broadly oblong in shape, and smooth along their margins. The upper leaf surface is pale-medium to dark green and hairless above, while the lower leaf surface is densely covered with woolly hairs that are very short. There is a prominent central vein along the length of each leaf, and finer side veins that radiate outward toward the smooth margins. When either the central stem or leaves are torn, a milky sap oozes out that has variable toxicity in the form of cardiac glycosides.

Umbels of flowers, each about 2½-4" across, emerge from the axils of the upper leaves. These flowers are quite fragrant, with a scent resembling violets or pansies, and they range in color from faded light pink to reddish purple. Each flower is about ¼" across, consisting of 5 reflexed petals and 5 raised hoods with curved horns. The hoods are more light-colored than the petals. The pedicels of the flowers are light green to pale red and hairy. The blooming period lasts about 1-1½ months from early to mid-summer. The seedpods (follicles) are 3-4" long, broadly lanceoloid, and covered with soft prickles and short woolly hairs. At maturity, each seedpod split along one side to release numerous seeds that have large tufts of white hair. Dispersion of seed is by wind. The root system has long creeping rhizomes, promoting the vegetative spread of this plant.

Cultivation: The preference is full sun, rich loamy soil, and mesic conditions, but this robust plant can tolerate a variety of situations, including partial sun and a high clay or sand content in the soil. Under ideal conditions, Common Milkweed can become 6' tall and spread aggressively, but it is more typically about 3-4' tall. This plant is very easy to grow once it becomes established.

Range & Habitat: The native Common Milkweed occurs in every county of Illinois and it is quite common (see Distribution Map). Habitats include moist to dry black soil prairies, sand prairies, sand dunes along lake shores, thickets, woodland borders, fields and pastures, abandoned fields, vacant lots, fence rows, and areas along railroads and roadsides. This plant is a colonizer of disturbed areas in both natural and developed habitats.

Faunal Associations: The flowers are very popular with many kinds of insects, especially long-tongued bees, wasps, flies, skippers, and butterflies, which seek nectar. Other insect visitors include short-tongued bees, various milkweed plant bugs, and moths, including Sphinx moths. Among these, the larger butterflies, predatory wasps, and long-tongued bees are more likely to remove the pollinia from the flowers. Some of the smaller insects can have their legs entrapped by the flowers and die. Common Milkweed doesn't produce fertile seeds without cross-pollination. The caterpillars of Danaus plexippes (Monarch Butterfly) feed on the foliage, as do the caterpillars of a few moths, including Enchaetes egle (Milkweed Tiger Moth), Cycnia inopinatus (Unexpected Cycnia), and Cycnia tenera (Delicate Cycnia). Less common insects feeding on this plant include Neacoryphus bicrucis (Seed Bug sp.) and Gymnetron tetrum (Weevil sp.); see Insect Table for other insect feeders). Many of these insects are brightly colored – a warning to potential predators of the toxicity that they acquired from feeding on milkweed. Mammalian herbivores don't eat this plant because of the bitterness of the leaves and their toxic properties.

Photographic Location: The photographs were taken at Meadowbrook Park in Urbana, Illinois, and along a roadside ditch in Champaign, Illinois.

Comments: Depending on the local ecotype, Common Milkweed is highly variable in appearance. The color of the flowers may be highly attractive, or faded and dingy-looking. This plant is often regarded as a weed to be destroyed, but its flowers and foliage provide food for many kinds of insects. Common Milkweed can be distinguished from other milkweeds by its prickly follicles (seedpods) – other Asclepias spp. within Illinois have follicles that are smooth, or nearly so.

Umbels of flowers, each about 2½-4" across, emerge from the axils of the upper leaves. These flowers are quite fragrant, with a scent resembling violets or pansies, and they range in color from faded light pink to reddish purple. Each flower is about ¼" across, consisting of 5 reflexed petals and 5 raised hoods with curved horns. The hoods are more light-colored than the petals. The pedicels of the flowers are light green to pale red and hairy. The blooming period lasts about 1-1½ months from early to mid-summer. The seedpods (follicles) are 3-4" long, broadly lanceoloid, and covered with soft prickles and short woolly hairs. At maturity, each seedpod split along one side to release numerous seeds that have large tufts of white hair. Dispersion of seed is by wind. The root system has long creeping rhizomes, promoting the vegetative spread of this plant.

Cultivation: The preference is full sun, rich loamy soil, and mesic conditions, but this robust plant can tolerate a variety of situations, including partial sun and a high clay or sand content in the soil. Under ideal conditions, Common Milkweed can become 6' tall and spread aggressively, but it is more typically about 3-4' tall. This plant is very easy to grow once it becomes established.

Range & Habitat: The native Common Milkweed occurs in every county of Illinois and it is quite common (see Distribution Map). Habitats include moist to dry black soil prairies, sand prairies, sand dunes along lake shores, thickets, woodland borders, fields and pastures, abandoned fields, vacant lots, fence rows, and areas along railroads and roadsides. This plant is a colonizer of disturbed areas in both natural and developed habitats.

Faunal Associations: The flowers are very popular with many kinds of insects, especially long-tongued bees, wasps, flies, skippers, and butterflies, which seek nectar. Other insect visitors include short-tongued bees, various milkweed plant bugs, and moths, including Sphinx moths. Among these, the larger butterflies, predatory wasps, and long-tongued bees are more likely to remove the pollinia from the flowers. Some of the smaller insects can have their legs entrapped by the flowers and die. Common Milkweed doesn't produce fertile seeds without cross-pollination. The caterpillars of Danaus plexippes (Monarch Butterfly) feed on the foliage, as do the caterpillars of a few moths, including Enchaetes egle (Milkweed Tiger Moth), Cycnia inopinatus (Unexpected Cycnia), and Cycnia tenera (Delicate Cycnia). Less common insects feeding on this plant include Neacoryphus bicrucis (Seed Bug sp.) and Gymnetron tetrum (Weevil sp.); see Insect Table for other insect feeders). Many of these insects are brightly colored – a warning to potential predators of the toxicity that they acquired from feeding on milkweed. Mammalian herbivores don't eat this plant because of the bitterness of the leaves and their toxic properties.

Photographic Location: The photographs were taken at Meadowbrook Park in Urbana, Illinois, and along a roadside ditch in Champaign, Illinois.

Comments: Depending on the local ecotype, Common Milkweed is highly variable in appearance. The color of the flowers may be highly attractive, or faded and dingy-looking. This plant is often regarded as a weed to be destroyed, but its flowers and foliage provide food for many kinds of insects. Common Milkweed can be distinguished from other milkweeds by its prickly follicles (seedpods) – other Asclepias spp. within Illinois have follicles that are smooth, or nearly so.

0

0

成长记

kensong

2018年07月10日

I usually pinch of Coleus flowers but seemed to have missed this one. Pretty too.

1

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年07月05日

A ripe rind is one sign a butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata) is ready to pick, and there are other signs. An annual winter squash vine, butternut squash grows 3/4 to 1 1/2 feet tall with a vine 10 to 15 feet long. Creamy-white to orange-yellow flowers appear in late spring and orange-fleshed fruits develop, which ripen in fall. Changes in the vine and changes in the color and texture of the fruit are some signs to look for that tell you butternut squash is ready for harvesting.

Days From Sowing

Providing severe weather conditions such as drought or prolonged cold temperatures don't occur, butternut squash fruits ripen a predictable number of days after sowing. In regular growing conditions, it takes 80 to 100 days after the seed was sown.

Drought stresses plants, and may speed up ripening. However, cold weather slows down butternut squash growth, and then fruit may ripen later than expected.

Vine Condition

When butternut squash fruits are ready for picking, the vine has done its job. It stops growing and begins to die back. If your butternut squash vine stops producing new shoots and leaves, and the existing leaves begin to yellow and wilt, the fruit is probably nearly ripe.

Skin Appearance

Butternut squash skin is light whitish-green, smooth and shiny while the fruit is growing. As they ripen, the fruits turn deep tan and become dull and dry.

Skin Texture

A change in skin texture is another sign of ripeness in butternut squash. Slightly soft when the fruit is growing, butternut squash skin becomes very tough when the fruit is ripe.

Harvest Time

When butternut squash fruit are ready to harvest, cut the stems with pruning shears or a sharp knife.

Cut the squash stems 1 inch from the fruit, and put them in a cool, dark, dry place. Don't allow the fruit to touch each other. Store the squash at 50 degrees Fahrenheit and 50 to 75 percent humidity and it will keep for two to three months. Check the fruit every one or two weeks, and remove and discard any that look diseased or have begun to decay.

Days From Sowing

Providing severe weather conditions such as drought or prolonged cold temperatures don't occur, butternut squash fruits ripen a predictable number of days after sowing. In regular growing conditions, it takes 80 to 100 days after the seed was sown.

Drought stresses plants, and may speed up ripening. However, cold weather slows down butternut squash growth, and then fruit may ripen later than expected.

Vine Condition

When butternut squash fruits are ready for picking, the vine has done its job. It stops growing and begins to die back. If your butternut squash vine stops producing new shoots and leaves, and the existing leaves begin to yellow and wilt, the fruit is probably nearly ripe.

Skin Appearance

Butternut squash skin is light whitish-green, smooth and shiny while the fruit is growing. As they ripen, the fruits turn deep tan and become dull and dry.

Skin Texture

A change in skin texture is another sign of ripeness in butternut squash. Slightly soft when the fruit is growing, butternut squash skin becomes very tough when the fruit is ripe.

Harvest Time

When butternut squash fruit are ready to harvest, cut the stems with pruning shears or a sharp knife.

Cut the squash stems 1 inch from the fruit, and put them in a cool, dark, dry place. Don't allow the fruit to touch each other. Store the squash at 50 degrees Fahrenheit and 50 to 75 percent humidity and it will keep for two to three months. Check the fruit every one or two weeks, and remove and discard any that look diseased or have begun to decay.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年06月29日

1.Ice Plants

Ice plants are an interesting genus of succulents, with daisy-like flowers. There is a good amount of variety among ice plants; some are low growing spreaders, others become bushy subshrubs. There are over 150 species in this genus from southern Africa. Most are easy growers that bloom freely. The botanical name, Lampranthus, is from the Greek words "Lampros" (bright) and anthos (flower).

Leaves: The stocky leaves grow in pairs and can be cylindrical or almost triangular. They are short, very succulent and often blue-green.

Flowers: Daisy-like flowers with thin petals that only open in the sun. Different species bloom in vivid shades of yellow, orange, pink and red. The flowers form near the stem tips. Some varieties bloom over a long period, others only a few weeks.

Botanical Name

Lampranthus species and hybrids

Common Names

Ice Plant. You may see individual species labeled as Ice Plants and some have quantifiers like Trailing Ice Plant. It can be confusing. If you are looking for a specific plant, you would be wise to have the botanical name.

Cold Hardiness

Hardiness will vary with the species and variety, but most are only perennial in USDA Hardiness Zones 8 - 10. Some species can tolerate a light frost, but despite their name, prolonged periods of cold, damp conditions will cause them to rot. Gardeners in colder areas can grow them as annuals or houseplants.

Sun Exposure

All varieties of ice plant grow and bloom best in full sun.

Mature Plant Size

The size will vary among the species, but most of the commonly grown ice plant varieties remain 2 ft. (60 cm) tall or lower, with a spreading habit.

Bloom Time

Many ice plants put on their best show in spring, with sporadic repeat blooms throughout the season, however, a few, like Lampranthus spectabilis, bloom all summer.

Suggested Varieties of Ice Plant

Lampranthus aurantiacus - Spring blooming, upright plant with bright orange petals around a yellow center. H 2 ft. (60 cm)

Lampranthus coccineus / Redflush Ice Plant - Bright red flowers throughout the season. Somewhat frost tolerant. H 2 ft. (60 cm)

Lampranthus haworthii - Blue-green leaves held up like a candelabra are covered with pink or purple flowers in the spring. Repeat blooms sporadically. H 2 ft. (60 cm)

Lampranthus spectabilis /Trailing Ice Plant- Long blooming in white or purple-pink. Low growing and spreading. H 2 ft. (60 cm)

Design Suggestions Using Ice Plant

Where the plants are hardy, they make a nice ground cover. Ice plants thrive in poor soil and make a wonderful alpine or rock garden plant or tucked in a stone wall. Their spreading habit means they quickly fill a container and spill over, so they are equally nice in hanging baskets and free-standing containers.

2.Growing and Caring for Ice Plants

Ice Plant Growing Tips

Soil: A neutral soil pH is fine, but it is more important to provide sandy, well-draining soil. Plants will rot if left in wet or damp soil for prolonged periods of time.

Planting: Ice Plants can be grown from either seed or cuttings. Seeds need warm temperatures (55 F.) to germinate. Taking cuttings is the fastest method. Make cuttings while the plant is actively growing, from spring to early fall. Cut shoots about 3 - 6 inches long and remove all but the top set of leaves.

Succulent cuttings should be allowed to dry slightly and callus. Leave them out in the air for several hours or overnight. Then root in sandy soil, in containers. Keep the soil evenly moist, until the cutting root. You can tell they have rooted by gently tugging on them. If they offer resistance, they have rooted and can be potted up.

Caring for Ice Plants

Established plants are extremely drought tolerant, however, they do prefer regular weekly watering during the summer. Allow the soil to dry out between waterings in the winter, when they are somewhat dormant.

Flowering is more abundant if container grown plants are fed a balanced fertilizer, according to label directions. In-ground plants should be fed if the soil is poor or if blooming is sparse.

Plants can be divided or repotted in early spring.

Pests & Problems of Ice Plants

Weather is the biggest problem when growing Ice Plants. Few diseases have been reported, but mealy bug and scale can occasionally infest.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年06月25日

6.Kalanchoe

So many of us only know these Kalanchoe as houseplants, forced into bloom at the florists. There are several hybrids with different forms, but all have flowers in clear, bright colors. Kalanchoe blossfeldiana is one of the most readily available. It can do quite well indoors but has the annoying habit of growing long and gangly and not wanting to flower again. When that happens,take a few cuttings and start over. It is frost tender.

7.Ice Plants (Lampranthus)

There are about 100 species of Lampranthus, succulents plants from South Africa. They have bright colored daisy-like flowers. The best known is the Ice Plant, Lampranthus multiradiatus. These look best massed and where they are hardy, they make a great ground cover or turf alternative, although I wouldn't walk on them. They are very forgiving. If you forget to water them, they just kept on blooming.

8.Sedum (stonecrop)

The tall Sedums, like ‛Autumn Joy' are wonderful showy, drought tolerant plants. Most bloom in late summer but look great for weeks as their broccoli-like flowers fill out. Even after blooming, the flowers just deepen in color and continue putting on a show. The creeping and trailing varieties have long been used in rock gardens and as ground covers. And they will cover ground very quickly. They have star-shaped blooms during the summer and are less attractive to deer than the tall varieties. You may see rabbits munching on them, though, probably for the water. Many varieties are extremely cold hardy.

9.Sempervivum

Hen and chicks have made a huge comeback. I remember them in my grandmother's garden and thought they were interesting, but not real flowers. I have become a total convert and enjoy spotting them tucked in throughout other's gardens.

Sempervivums are cold hardy, but a little touchy about long, hot, dry summers. They are perfect for all kinds of containers, from hypertufa troughs to strawberry jars.

These look a lot like Echeverias, but Sempervivum have pointed leaves that are a little thinner than Echeveria and they are more spherical.

10.Senecio

This is an odd group of plants, with bizarre shapes. The Candle Plants, Senecio articulatus, looks more like fingers, to me. Senecio talinoides var.mandraliscae, Blue Fingers, is icy blue-gray and these fingers are pointed. Then there's the perfectly charming Golden Groundsel, Senecio aureus, a ground cover with bright yellow, daisy-like flowers atop base rosettes. It's also hardy down to USDA Zone 4. Senecio rowleyanus (String of Beads or String of Pearls) looks more like a string of peas, but whatever it's called, it's striking.

So many of us only know these Kalanchoe as houseplants, forced into bloom at the florists. There are several hybrids with different forms, but all have flowers in clear, bright colors. Kalanchoe blossfeldiana is one of the most readily available. It can do quite well indoors but has the annoying habit of growing long and gangly and not wanting to flower again. When that happens,take a few cuttings and start over. It is frost tender.

7.Ice Plants (Lampranthus)

There are about 100 species of Lampranthus, succulents plants from South Africa. They have bright colored daisy-like flowers. The best known is the Ice Plant, Lampranthus multiradiatus. These look best massed and where they are hardy, they make a great ground cover or turf alternative, although I wouldn't walk on them. They are very forgiving. If you forget to water them, they just kept on blooming.

8.Sedum (stonecrop)

The tall Sedums, like ‛Autumn Joy' are wonderful showy, drought tolerant plants. Most bloom in late summer but look great for weeks as their broccoli-like flowers fill out. Even after blooming, the flowers just deepen in color and continue putting on a show. The creeping and trailing varieties have long been used in rock gardens and as ground covers. And they will cover ground very quickly. They have star-shaped blooms during the summer and are less attractive to deer than the tall varieties. You may see rabbits munching on them, though, probably for the water. Many varieties are extremely cold hardy.

9.Sempervivum

Hen and chicks have made a huge comeback. I remember them in my grandmother's garden and thought they were interesting, but not real flowers. I have become a total convert and enjoy spotting them tucked in throughout other's gardens.

Sempervivums are cold hardy, but a little touchy about long, hot, dry summers. They are perfect for all kinds of containers, from hypertufa troughs to strawberry jars.

These look a lot like Echeverias, but Sempervivum have pointed leaves that are a little thinner than Echeveria and they are more spherical.

10.Senecio

This is an odd group of plants, with bizarre shapes. The Candle Plants, Senecio articulatus, looks more like fingers, to me. Senecio talinoides var.mandraliscae, Blue Fingers, is icy blue-gray and these fingers are pointed. Then there's the perfectly charming Golden Groundsel, Senecio aureus, a ground cover with bright yellow, daisy-like flowers atop base rosettes. It's also hardy down to USDA Zone 4. Senecio rowleyanus (String of Beads or String of Pearls) looks more like a string of peas, but whatever it's called, it's striking.

0

1

成长记

Pommy Mommy

2018年06月20日

I'm pleasantly surprised that this hydrangea bloomed any flowers this year especially since I just planted it last summer

2

0

成长记

Pommy Mommy

2018年06月07日

Strawberries have sprouted a few more flowers and a few green berries are turning red.

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年06月05日

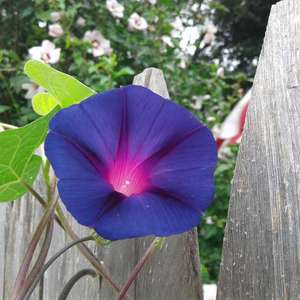

Description: This perennial wildflower consists of a low rosette of basal leaves spanning about 4-6" across, from which stalks of flowers develop directly from the crown. The blades of the basal leaves are up to 2½" long and across; for var. dilatata, they are usually divided into 5-7 palmate lobes. These lobes are finger-like in shape, somewhat variable in size, and extend up to half-way into the blade. Some of the larger lobes may be subdivided into smaller lobes, and the margins of the leaf blade may have a few dentate teeth. The upper surface of each leaf blade is medium to dark green and hairless, while the lower surface is light green and hairy along the veins. The petiole of each leaf is about as long as the blade and rather stout; it is conspicuously hairy on the lower side. Individual flowers about ¾–1" across are borne at the apex of ascending stalks that are as long or longer than the leaves.

Each flower has 5 spreading petals that are deep blue-violet (2 upper, 2 lateral, and 1 lower), and 5 sepals that are light green to purple. The 2 lateral petals have dense white hairs (or beards) near the throat of the flower, while the lower petal has a conspicuous patch of white with blue-violet veins. These petals converge into a short nectar spur that is surrounded by the sepals. The sepals are lanceolate-ovate and pubescent. The stalk of each flower is densely covered with spreading white hairs; it is light green to deep purple, and nods downward at the apex where the flower occurs. The blooming period occurs during mid-spring to late spring and lasts about 2-3 weeks. During the summer, inconspicuous flowers are produced that are self-fertile; they are not pollinated by insects, unlike the spring flowers. Each fertile flower is replaced by an oblongoid capsule containing many small brown seeds. When it is ripe, this capsule divides into 3 parts, mechanically ejecting the seeds several inches or feet from the mother plant. The rootstock consists of a short stout crown with fibrous roots underneath.

Cultivation: The preference is dappled sunlight during the spring, followed by partial sun or light shade during the summer. The basal leaves die down during the fall. The soil should contain some loam and be well-drained; some rocky or gritty material is also tolerated. This plant dislikes competition from taller ground vegetation.

Range & Habitat: This variety of Cleft Violet is uncommon in the southern two-thirds of Illinois, while in the rest of the state it is rare or absent (see Distribution Map). Local populations tend to be widely scattered from each other. Habitats include dry rocky woodlands, wooded upper slopes, and thinly wooded bluffs. Oak trees are often present at these habitats. The Cleft Violet is normally found in higher quality woodlands where the original ground flora is intact.

Faunal Associations: The flower nectar of violets attracts various bees (Andrenid bees, Mason bees, etc.), bee flies (Bombylius spp.), butterflies, and skippers. The caterpillars of several Fritillary butterflies and miscellaneous moths feed on the foliage of violets (see the Butterfly & Moth Table), as do the caterpillars of Ametastegia pallipes (Violet Sawfly), which skeletonize the leaves. The insect Odontothrips pictipennis (Thrips sp.) sucks juices from violets. The leaves and stems of violets are eaten to a limited extent by the Cottontail Rabbit, Eastern Chipmunk, Wild Turkey, and Ruffed Grouse; the seeds are eaten by the Slate-Colored Junco.

Photographic Location: The wildflower garden of the webmaster in Urbana, Illinois.

Comments: This variety of Cleft Violet is one of several violets with lobed leaves. In general, it is less deeply lobed than Viola pedata (Bird's Foot Violet) and Viola pedatifida (Prairie Violet), but more strongly lobed than Viola sagittata (Arrow-Leaved Violet) and Viola fimbriatula (Sand Violet). Even for a single plant of Cleft Violet, there can be significant variation on the number of lobes and their depth for each leaf. The flowers of this species are quite similar in appearance to those of other violets with blue-violet petals. Other common names of Viola palmata are Early Blue Violet and Blue Wood Violet. A scientific synonym for this species is Viola triloba dilatata. Where their ranges overlap, this variety of Cleft Violet may intergrade with the typical variety; the latter has fewer lobes on its leaves (usually 3 or none).

Each flower has 5 spreading petals that are deep blue-violet (2 upper, 2 lateral, and 1 lower), and 5 sepals that are light green to purple. The 2 lateral petals have dense white hairs (or beards) near the throat of the flower, while the lower petal has a conspicuous patch of white with blue-violet veins. These petals converge into a short nectar spur that is surrounded by the sepals. The sepals are lanceolate-ovate and pubescent. The stalk of each flower is densely covered with spreading white hairs; it is light green to deep purple, and nods downward at the apex where the flower occurs. The blooming period occurs during mid-spring to late spring and lasts about 2-3 weeks. During the summer, inconspicuous flowers are produced that are self-fertile; they are not pollinated by insects, unlike the spring flowers. Each fertile flower is replaced by an oblongoid capsule containing many small brown seeds. When it is ripe, this capsule divides into 3 parts, mechanically ejecting the seeds several inches or feet from the mother plant. The rootstock consists of a short stout crown with fibrous roots underneath.

Cultivation: The preference is dappled sunlight during the spring, followed by partial sun or light shade during the summer. The basal leaves die down during the fall. The soil should contain some loam and be well-drained; some rocky or gritty material is also tolerated. This plant dislikes competition from taller ground vegetation.

Range & Habitat: This variety of Cleft Violet is uncommon in the southern two-thirds of Illinois, while in the rest of the state it is rare or absent (see Distribution Map). Local populations tend to be widely scattered from each other. Habitats include dry rocky woodlands, wooded upper slopes, and thinly wooded bluffs. Oak trees are often present at these habitats. The Cleft Violet is normally found in higher quality woodlands where the original ground flora is intact.

Faunal Associations: The flower nectar of violets attracts various bees (Andrenid bees, Mason bees, etc.), bee flies (Bombylius spp.), butterflies, and skippers. The caterpillars of several Fritillary butterflies and miscellaneous moths feed on the foliage of violets (see the Butterfly & Moth Table), as do the caterpillars of Ametastegia pallipes (Violet Sawfly), which skeletonize the leaves. The insect Odontothrips pictipennis (Thrips sp.) sucks juices from violets. The leaves and stems of violets are eaten to a limited extent by the Cottontail Rabbit, Eastern Chipmunk, Wild Turkey, and Ruffed Grouse; the seeds are eaten by the Slate-Colored Junco.

Photographic Location: The wildflower garden of the webmaster in Urbana, Illinois.

Comments: This variety of Cleft Violet is one of several violets with lobed leaves. In general, it is less deeply lobed than Viola pedata (Bird's Foot Violet) and Viola pedatifida (Prairie Violet), but more strongly lobed than Viola sagittata (Arrow-Leaved Violet) and Viola fimbriatula (Sand Violet). Even for a single plant of Cleft Violet, there can be significant variation on the number of lobes and their depth for each leaf. The flowers of this species are quite similar in appearance to those of other violets with blue-violet petals. Other common names of Viola palmata are Early Blue Violet and Blue Wood Violet. A scientific synonym for this species is Viola triloba dilatata. Where their ranges overlap, this variety of Cleft Violet may intergrade with the typical variety; the latter has fewer lobes on its leaves (usually 3 or none).

0

0

文章

Miss Chen

2018年06月05日

Description: This perennial wildflower is 4-8" in length (or longer), consisting of leafy stems with axillary flowers and seed capsules. The stems are light green and glabrous. The blades of alternate leaves are about 1-2½" long and ¾-1½" across; they are oval-cordate in shape and serrate-crenate along their margins. The base of each leaf blade is indented, while its tip is well-rounded to somewhat pointed. The upper blade surface is medium to dark green and glabrous, while the lower surface to light to medium green and glabrous. The slender petioles are about the same length as the leaf blades or shorter; they are light green and glabrous. At the base of each petiole, there is a pair of stipules up to ½" long. These stipules are linear-lanceolate in shape and coarsely toothed along their margins. Individual flowers develop from the axils of the leaves on slender pedicels about 1½-3" long; the flowers are usually held above the leaves. The pedicels are light green and glabrous; there is a pair of small linear bracts toward the middle of each pedicel.

Individual flowers are ½-¾" across, consisting of 5 pale blue-violet petals, 5 green sepals, and the reproductive organs. The style of each flower is bent downward at its tip, where it is not swollen. Dark blue-violet veins radiate away from the throat of each flower across the petals; the two lateral petals have tufts of white hair (or beards) toward their bases. The lower petal has a relatively long nectar spur about ¼" long; this spur is sometimes visible when the flower is viewed from the front (behind the upper 2 petals). The nectar spur is relatively stout and either straight or slightly hooked. The sepals are linear-lanceolate, sometimes toothed toward their bases, and hairless. The blooming period occurs during the middle of spring for about 1 month. Fertilized flowers produce an ovoid-oblongoid seed capsule about 1/3" long. This capsule splits open into 3 parts to fling the seeds from the mother plant. This wildflower also produces inconspicuous cleistogamous flowers during the summer, which are self-fertile; their seed capsules are similar to the earlier fertilized flowers. The small seeds are globoid in shape and light brown at maturity. The root system consists of a vertical crown with fibrous roots and horizontal rhizomes; clonal offsets are produced occasionally from the rhizomes.

Cultivation: During the spring, the preference is dappled sunlight to light shade, moist conditions, and a rich loamy soil with abundant organic material. Later in the year, more shade is tolerated.

Range & Habitat: The native Dog Violet is found primarily in NE Illinois (see Distribution Map). This wildflower is considered rare and it is state-listed as 'threatened.' Habitats include moist rich woodlands, swampy woodlands, and moist meadows in wooded areas. Sometimes this violet is found in slightly sandy habitats that are similar to the preceding ones. Dominant canopy trees in these habitats are typically ash, maple, or elm. Dog Violet is found in higher quality habitats where the original ground flora is still intact.

Faunal Associations: In this section, information about floral-faunal relationships applies to Viola spp. (Violets) in general. The flowers of violets are cross-pollinated primarily by various bees, including honeybees, bumblebees, Mason bees (Osmia spp.), Little Carpenter bees (Ceratina spp.), digger bees (Synhalonia spp.), Halictid bees, and Andrenid bees. One bee species, Andrena violae (Violet Andrenid Bee), is a specialist pollinator of violets. Other floral visitors include bee flies (Bombylius spp.), small butterflies, skippers, and ants. Most of these insects suck nectar from the flowers, although some of the bees also collect pollen. Other insects feed on the foliage and other parts of violets. These insect feeders include the caterpillars of several Fritillary butterflies (Euptoieta claudia, Boloria spp., Speyeria spp.) and the caterpillars of several moths, including Elaphria grata (Grateful Midget), Eubaphe mendica (The Beggar), and Apantesis nais (Nais Tiger Moth). Other insect feeders include the thrips Odontothrips pictipennis, the aphid Neotoxoptera violae, and the larvae of Ametastegia pallipes (Violet Sawfly). Vertebrate animals feed on violets only to a limited extent. The White-Tailed Deer, Cottontail Rabbit, and Wood Turtle (Clemmys insculpta) sometimes browse on the foliage, while the White-Footed Mouse eats the seeds. Birds that feed on violets include the Mourning Dove (seeds), Ruffed Grouse (seed capsules, foliage), and Wild Turkey (seed capsules, rhizomes).

Photographic Location: A damp area of Goll Woods in NW Ohio, and a swampy woodland at the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in NW Indiana.

Comments: This interesting species belongs to a small group of violets with blue-violet flowers, nectar spurs of above average length, and flowering leafy stems (as opposed to violets with basal leaves and flowers on separate non-leafy stalks). Aside from the Dog Violet, other species in this group include Viola labradorica (Alpine Violet), Viola adunca (Hook-Spurred Violet), and Viola walteri (Walter's Violet). While the Dog Violet has pale blue-violet flowers, these other violets often have medium to dark blue-violet flowers (among other minor differences). The Alpine Violet and Hook-Spurred Violet have a more northern boreal distribution, while Walter's Violet is more southern and Appalachian. None of these three species have been found in Illinois. Some authorities have proposed reducing the status of the Dog Violet to a variety of either the Alpine Violet or the Hook-Spurred Violet.

Individual flowers are ½-¾" across, consisting of 5 pale blue-violet petals, 5 green sepals, and the reproductive organs. The style of each flower is bent downward at its tip, where it is not swollen. Dark blue-violet veins radiate away from the throat of each flower across the petals; the two lateral petals have tufts of white hair (or beards) toward their bases. The lower petal has a relatively long nectar spur about ¼" long; this spur is sometimes visible when the flower is viewed from the front (behind the upper 2 petals). The nectar spur is relatively stout and either straight or slightly hooked. The sepals are linear-lanceolate, sometimes toothed toward their bases, and hairless. The blooming period occurs during the middle of spring for about 1 month. Fertilized flowers produce an ovoid-oblongoid seed capsule about 1/3" long. This capsule splits open into 3 parts to fling the seeds from the mother plant. This wildflower also produces inconspicuous cleistogamous flowers during the summer, which are self-fertile; their seed capsules are similar to the earlier fertilized flowers. The small seeds are globoid in shape and light brown at maturity. The root system consists of a vertical crown with fibrous roots and horizontal rhizomes; clonal offsets are produced occasionally from the rhizomes.

Cultivation: During the spring, the preference is dappled sunlight to light shade, moist conditions, and a rich loamy soil with abundant organic material. Later in the year, more shade is tolerated.

Range & Habitat: The native Dog Violet is found primarily in NE Illinois (see Distribution Map). This wildflower is considered rare and it is state-listed as 'threatened.' Habitats include moist rich woodlands, swampy woodlands, and moist meadows in wooded areas. Sometimes this violet is found in slightly sandy habitats that are similar to the preceding ones. Dominant canopy trees in these habitats are typically ash, maple, or elm. Dog Violet is found in higher quality habitats where the original ground flora is still intact.

Faunal Associations: In this section, information about floral-faunal relationships applies to Viola spp. (Violets) in general. The flowers of violets are cross-pollinated primarily by various bees, including honeybees, bumblebees, Mason bees (Osmia spp.), Little Carpenter bees (Ceratina spp.), digger bees (Synhalonia spp.), Halictid bees, and Andrenid bees. One bee species, Andrena violae (Violet Andrenid Bee), is a specialist pollinator of violets. Other floral visitors include bee flies (Bombylius spp.), small butterflies, skippers, and ants. Most of these insects suck nectar from the flowers, although some of the bees also collect pollen. Other insects feed on the foliage and other parts of violets. These insect feeders include the caterpillars of several Fritillary butterflies (Euptoieta claudia, Boloria spp., Speyeria spp.) and the caterpillars of several moths, including Elaphria grata (Grateful Midget), Eubaphe mendica (The Beggar), and Apantesis nais (Nais Tiger Moth). Other insect feeders include the thrips Odontothrips pictipennis, the aphid Neotoxoptera violae, and the larvae of Ametastegia pallipes (Violet Sawfly). Vertebrate animals feed on violets only to a limited extent. The White-Tailed Deer, Cottontail Rabbit, and Wood Turtle (Clemmys insculpta) sometimes browse on the foliage, while the White-Footed Mouse eats the seeds. Birds that feed on violets include the Mourning Dove (seeds), Ruffed Grouse (seed capsules, foliage), and Wild Turkey (seed capsules, rhizomes).

Photographic Location: A damp area of Goll Woods in NW Ohio, and a swampy woodland at the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in NW Indiana.

Comments: This interesting species belongs to a small group of violets with blue-violet flowers, nectar spurs of above average length, and flowering leafy stems (as opposed to violets with basal leaves and flowers on separate non-leafy stalks). Aside from the Dog Violet, other species in this group include Viola labradorica (Alpine Violet), Viola adunca (Hook-Spurred Violet), and Viola walteri (Walter's Violet). While the Dog Violet has pale blue-violet flowers, these other violets often have medium to dark blue-violet flowers (among other minor differences). The Alpine Violet and Hook-Spurred Violet have a more northern boreal distribution, while Walter's Violet is more southern and Appalachian. None of these three species have been found in Illinois. Some authorities have proposed reducing the status of the Dog Violet to a variety of either the Alpine Violet or the Hook-Spurred Violet.

0

0